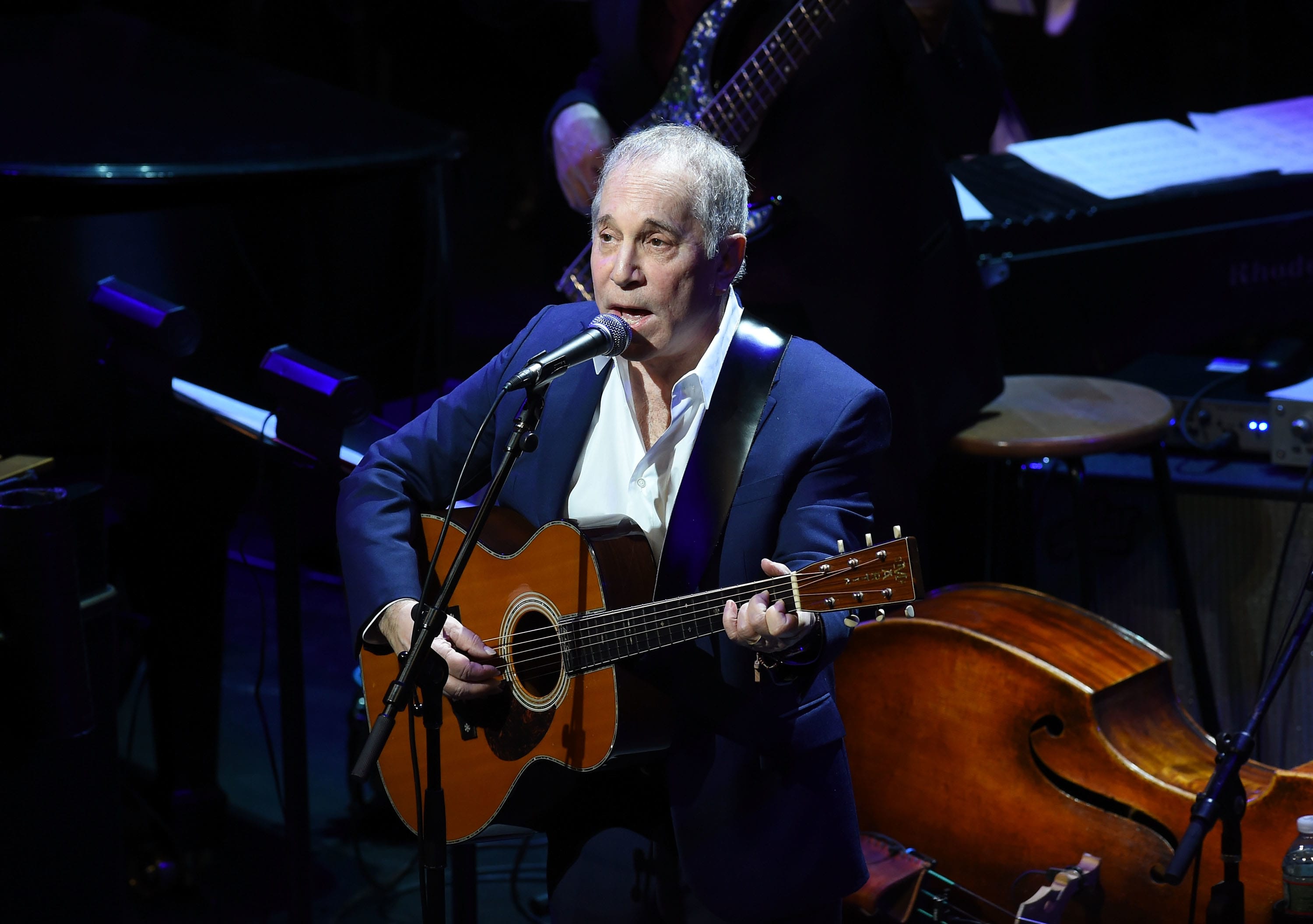

Paul Simon performs onstage at The Nearness Of You Benefit Concert at Frederick P. Rose Hall, Jazz at Lincoln Center on January 20, 2015 in New York City.

Ilya S. Savenok | Getty Images Entertainment | Getty images

From Bob Dylan plugging in his electric guitar for the first time to Super Bowl commercials, there have always been times in music history when the most seasoned fans accuse their idols of doing the unthinkable: sold out. But right now, “sold out” has a new connotation, and it’s a thriving market for both investors and superstars taking on artists.

A wave of boomer rock icons are selling from their song catalogs. The moves, the last of which was made by Paul Simon last week, point to a clear truth about the intersection of art and money: music has always been a business and a true creative genius deserved to be rewarded with wealth. And it is a company that is currently undergoing major changes as a result of streaming and further disruptions caused by the pandemic. The deals of Paul Simon, Bob Dylan, Neil Young (in Young’s case a 50% stake) and Stevie Nicks (80% of the rights to her songs) highlight important trends in the entertainment industry, capital markets and wealth management.

Music publishers such as Hipgnosis Songs Fund and Primary Wave Music, and conglomerate players such as BMG, Sony, Warner Music Group and Vivendi’s Universal Music Group, are buying up premium song catalogs in big deals fueled by record low interest rates with the belief that it will. more lucrative revenues in the future through the sale of the rights to these songs through entertainment platforms.

Record low rates fuel music deals

Larry Mestel, CEO of Primary Wave Music, the company that has just acquired a majority stake in the catalog of the two-time Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductee, Stevie Nicks, told CNBC that the economic environment created by the Coronavirus pandemic is favorable. worked out. of companies looking to buy large assets. These low interest rates make it easier to borrow money, and the high yield has created a perfect opportunity for buyers.

“You’re talking about a low-interest environment and you can get a 7% to 9% … and then increase that through marketing and generate mid-teen returns. That’s a very attractive place for it. people to bet money, ”he said.

Music catalogs have also proven to be recession-proof, and the pandemic has only increased the number of deals being struck as the music industry is experiencing a massive disruption due to the closing of live stages and touring.

Music streaming is on the rise

The deals also come at a time when streaming music – despite all the controversy and skepticism on the part of the musicians themselves about getting a rough deal – has proven to be an economic juggernaut, at least for the record labels. In 2020, Goldman Sachs predicted global music revenue would reach $ 142 billion by the end of the decade, representing an 84% increase from the $ 77 billion level in 2019 and streaming 1.2 billion users by 2030, four times the level in 2019. and mainly benefited companies like Sony, which bought Simon’s catalog, and Universal, which bought Dylan’s songs.

Global streaming music revenues hit an all-time high as a percentage of the industry last year (83% according to a recent report) and it’s also in favor of the superstars. Spotify has said its mission is “to give a million creative artists a chance to make a living from their art,” but as a recent New York Times analysis noted, Spotify’s data shows that last year was only about $ 13,000. Generated 50,000 or more in payments.

However, it is not just streaming. The rights to catalogs of larger acts, once acquired, can be used in synchronized placements that license music on a variety of media, including film, television shows, advertisements, and video games.

“From a publisher’s perspective, it is extremely valuable to obtain the rights to a particular catalog that we can pitch for synchronization,” said Rebecca Valice, copyright and license manager at PEN Music Group. “A catalog can do its own pitching because of its legendary success.”

Appreciate rock icons

The more recognizable a catalog is, the more valuable it becomes for companies to buy and use in movies or television. The best catalogs “pay for themselves” over time, she says, because synchronization helps recoup the money buyers spent “and then some as time goes by.”

“I really believe the icons and legends are worth more than the other artists,” said Mestel. Primary Wave owns the catalogs of such stars as Whitney Houston, Ray Charles and Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons.

Some famous boomer-era musicians have lashed out at the situation the industry has placed them in, such as David Crosby, who tweeted in December, “I’m selling mine too … I can’t work … and streaming stole my record money … I have a family and a mortgage and I have to take care of them, so it’s my only option … I’m sure the others feel the same. “

He sold his entire catalog in March to Irving Azoff’s Iconic Artists Group, which had also recently acquired a majority stake in The Beach Boys’ intellectual property, including part of the song catalog.

“Given our current inability to work live, this deal is a boon to me and my family and I truly believe these are the best people to do it with,” Crosby said in a statement announcing the deal.

Boomer generation estate planning

For the musicians themselves, a mega trend is at work: the wealth planning needs of America’s richest generation. Boomer musicians (and those just born on the eve of that generation’s start, like Simon and Dylan in 1941), like their fans, are getting older. “Artists are getting older now, so they can use cash, they can make wealth plans,” says Mestel.

The downside, of course, could be the loss of control over an artist’s most precious asset: the creative genius who made their career.

“These aging rock stars may want to make money to look after their estates … but you will lose control over your brand and your legacy to some degree, depending on the protections you put in place as part of the deal,” he said. John Ozszajca, musician and founder of Music Marketing Manifesto, a company that teaches musicians how to sell and market their music.

Crosby and Azoff have been friends for a long time, a point Azoff made in the release announcing the deal.

It seems like everyone in a relationship in the music business knows that someone is trying to raise money.

Larry Mestel

CEO of Primary Wave Records

Some fans aren’t too happy hearing hits like Nicks’ Edge of Seventeen or Dylan’s’ Like a Rolling Stone ‘selling cars and clothing – although Dylan has been making Super Bowl commercials for GM and IBM for many years, and his songs have only been heard in others – but the decisions to sell catalogs can also help musicians avoid posthumous legal battles like the estates of Tom Petty, Prince and Aretha Franklin had to endure.

BMG acquired the catalog interests of Nicks’ bandmate, Mick Fleetwood, from Fleetwood Mac early this year and noted some stats in its announcement that show that no matter how old boomer acts are, they can get a new lease of life from viral streaming hits. The Fleetwood Mac song ‘Dreams’ generated more than 3.2 billion streams worldwide (over an eight-week period from September 24 to November 19, 2020) thanks to a video featuring a cranberry juice fan, introducing a new generation, more accustomed to TikTok, to Fleetwood Mac. The band’s album “Rumors” reached number 6 on the Billboard Streaming Songs chart 43 years after its release.

Dylan’s deal is the largest reported to date, valued at $ 300 million, although no sale price was officially announced and Universal only said in a release that it was “the most important music publishing deal of this century.”

Mestel believes that the boom is not nearing an end.

“It seems like everyone in a relationship in the music business knows that someone is trying to raise money. But that doesn’t mean they can start looking for assets to sell them or even know what they’re doing.”

BMG and private equity giant KKR recently signed a deal to go out and make a major musical rights acquisition, and as one executive told Rolling Stone, “We’re not chasing hits from January 2021. We’re looking at repertoire that has proven itself to be part of our lives. “

KKR has struck big music deals in the past, and the trend of buying rights is not new, but the current boom is remarkable and fits in with the asset class appreciation that is taking place in so many parts of the market as investors seek more ways. to put their money to work. While the boomer deals are the biggest headlines, recent acts are also seeing big payouts. Earlier this year, KKR bought a stake in OneRepublic’s Ryan Tedder catalog for a reportedly high sum.

Companies like Primary Wave have partnered with artists like Nicks to keep them as part of the deal and make that deal even better for them in the future, said Mestel, who says many didn’t understand they could make a deal. partnership, sell a piece of their catalog, and that piece may become more valuable in the future than the 100% they previously owned.

“If all goes well, [artists] get the most out of what they’re trying to sell it for, and it’s usually a win-win scenario for the buyer and seller, ”said Valice.