Washington- When an otherwise healthy 48-year-old Nebraska woman came to the emergency room after three days of stomach aches and pains, doctors uncovered a life-threatening conundrum. His platelets, the colorless blood cells that clump together to form clots, had collapsed. But a CT scan of her abdomen and pelvis revealed large blood clots, The Washington Post reported.

His medical team was quick to unravel the seemingly paradoxical combination of symptoms. Even when the patient was treated with a common blood thinner, more clots appeared in her brain and in the blood vessels around her liver and spleen.

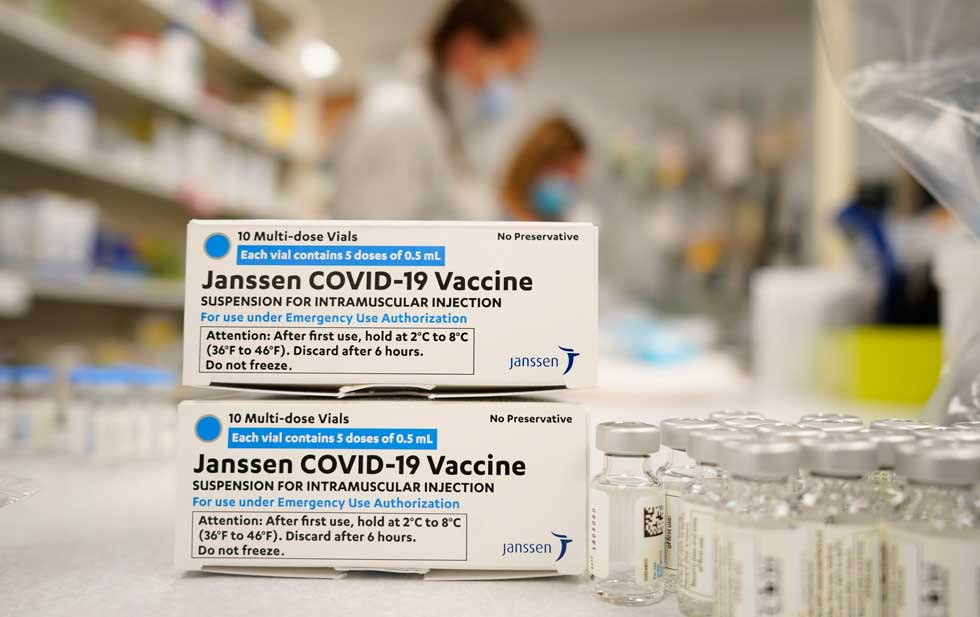

As doctors searched for clues in the patient’s medical history, a seemingly innocent fact emerged: She had been given the Johnson & Johnson coronavirus vaccine two weeks before she started feeling ill.

Between March 19 and April 12, medical teams from Virginia to Nevada found the same puzzling constellation of symptoms in five other women ages 18 to 48. All had recently received the Johnson & Johnson vaccine. One woman died.

Last Tuesday, US health officials recommended that those vaccines be paused so experts can rethink how and if the vaccine could be used safely. Only six cases were known of the more than 7 million injections, but the symptoms the women experienced were alarming as they were severe and virtually invisible in healthy people, with one recent exception. They were similar to the cases in Europe among people who received a similar coronavirus vaccine developed by AstraZeneca and the University of Oxford.

Understanding the rare and potentially related side effects after vaccination can be notoriously complicated, but in this case, U.S. health officials have a plan. European scientists’ detective work in similar cases in March, coupled with decades of painstaking research into an obscure immune response to the blood-thinning drug heparin, provided them with a likely, but not certain, mechanism just weeks after the cases began to develop. detected.

Scientific questions remain about which component of vaccines could trigger the response and who is at risk. But the syndrome is so similar to rare heparin-related reactions that scientists have given the vaccine-induced response a similar name, established a likely link, and identified a widely available diagnostic test. Obviously, heparin shouldn’t be given as it can worsen clots, but there are other treatments on the shelves of almost every hospital, although they can’t repair the damage caused by severe clots.

In a letter sent to the New England Journal of Medicine Friday, Johnson & Johnson scientists said that “the evidence is insufficient to establish a causal relationship” between the injection and clots, and asked for more evidence to support the clarify symptoms seen in people who had been vaccinated. But many experts, including U.S. government health officials, said the immune statement is the leading theory.

On Monday, the director of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Rochelle Walensky, said health officials were examining “a handful” of additional cases to assess whether it was the same rare reaction. Understanding the frequency of events will help make decisions about how to use the vaccine.

“I find it encouraging that it was not an overwhelming number of cases,” said Walenksy.