The way things behave in microgravity may seem obvious to us now, after humans ventured into space for over 50 years.

But we have not always been sure how space can affect certain things. Just like fire. Or planar worms. Or even plants. Only by conducting experiments can we learn the answers to these burning questions.

That has led to some pretty fascinating, sometimes disturbing and sometimes downright crazy experiments that have been conducted in space.

A spacesuit is slid out of an airlock

The video above plays out like something out of a nightmare. A spacesuit floats, unbound, away from the International Space Station), while the vast black void of space yawns in front of it.

You may be relieved that no people were harmed in the making of this experiment – there is no one in the Russian Orlan spacesuit, nicknamed Ivan Ivanovitch or Mr Smith – it is packed with a ton of old clothes and a radio station.

The idea was that old space suits could be used as satellites. SuitSat-1 – officially designated AMSAT-OSCAR 54 – was deployed on February 3, 2006, but the experiment was only partially successful; reports vary, with NASA claiming the station died shortly after release and Russia reporting a final broadcast a fortnight later. The last confirmed signal was received on February 18.

SuitSat-1 then spent several months in silent orbit before entering Earth’s atmosphere and burning on September 7, 2006.

The hammer and the feather

At the end of the 16th century, Galileo Galilei dropped two spheres of unequal mass from the Leaning Tower of Pisa in Italy. When both hit the ground at the same time, he had countered classically established beliefs by showing that mass had no influence on gravitational acceleration. All objects, regardless of mass, should fall at the same speed – even if it is a spring and a hammer.

This is difficult to demonstrate on Earth because of air resistance. But nearly 400 years later, a human standing on the moon repeated the experiment.

On August 2, 1971, Apollo 15 Commander David Scott took a geological hammer in one hand and a falcon feather in the other. He lifted them to a height of about six feet above the ground and dropped them. Since the astronaut was essentially in a vacuum, the two objects with no air resistance fell in sync.

“Within the accuracy of the simultaneous release, the objects were observed to undergo the same acceleration and simultaneously hit the lunar surface,” wrote NASA astronaut Joe Allen, “which was a result predicted by an established theory, yet a reassuring result both. the number of viewers who witnessed the experiment as well as the fact that the journey home was critically based on the validity of the particular theory being tested. “

The hammer and spring are both still there.

Carbonated tablet in a dollop of water

In microgravity, if you squirt a little bit of water out of a nozzle, it just hangs there, gooey and wobbly.

This can be a lot of fun. Experiments and demonstrations include popping water balloons in the vomit comet (the plane that makes parabolic flights to create short periods of free fall) and the ISS, attaching a blob of water with a large bubble to a speaker to observe the vibrations , and put a GoPro camera in a blob of water to film it from the inside (you’ll want stereoscopic 3D glasses for that).

In 2015, astronaut Scott Kelly colored a water bubble with food coloring, then inserted effervescent tablets and watched them dissolve and release gases into the water. It was filmed with the space station’s new 4K camera, so you can watch the whole alien algae-spawning … thing in gloriously crisp resolution.

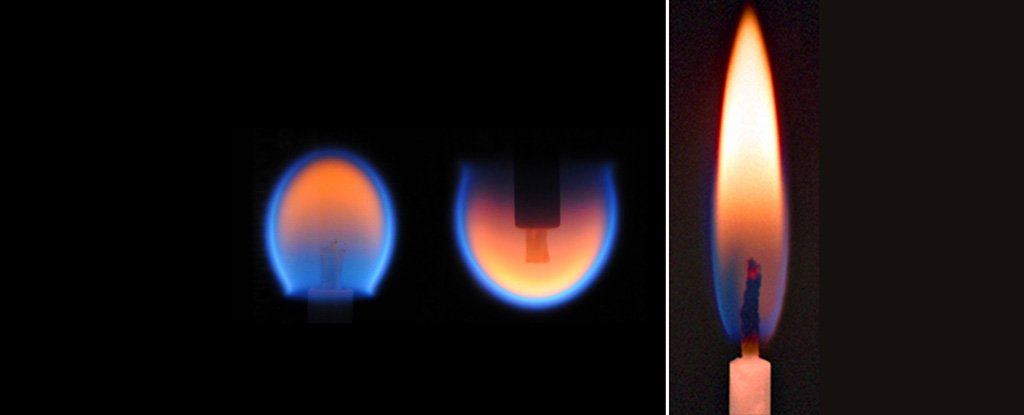

Fire in space

(ESA / NASA)

(ESA / NASA)

Just as water behaves differently in microgravity, so does fire. Fortunately, the 1997 fire of the Mir space station has been a one-off event so far, but figuring out how fire behaves in microgravity can help plan fire safety for future long-term missions, such as the manned mission to Mars and the permanent Moon. base. It can also help to inform fire safety protocols here on Earth.

To this end, a number of ongoing research projects have studied what happens to flames in space. The combustion and suppression of solids on board the ISS have explored the combustion and extinction properties of a wide variety of fuel types in microgravity. Data from these experiments can be used to build more complex models to understand the finer details of combustion in Earth’s gravity.

On board the Cygnus cargo spacecraft, scientists investigated how flames behave under different space travel conditions in the Saffire experiments. And NASA’s Flame Design study – part of the Advanced Combustion through Microgravity Experiments – examines soot production and control.

All of which is of course very useful and interesting. But it’s also insanely beautiful, and we bet some astronauts love playing with fire in space.

Spinning space

In 2011, scientists began to answer the burning question: Can spiders adapt to space travel? They sent two golden silk orb weaver spiders (Trichonephila clavipes), Esmeralda and Gladys, for a stay of 45 days aboard the ISS.

They were kept in a beautiful habitat (can you imagine spiders sitting loose on a space station), with lighting conditions to simulate a night-day cycle, temperature and humidity control, and a healthy diet of juicy fruit flies.

Both spiders adapted beautifully, continued to spin their webs and hunt for their food. Orb weavers eat their webs at the end of each day to reclaim protein, and spin them again in the morning; this too the spiders continued to do as planned, which was interesting as different kinds of globe weavers on the ISS were simply spinning their webs at any old time of the day.

But not everything was completely normal. In microgravity, the spiders spun their webs differently – flatter and rounder, compared to the more three-dimensional, asymmetrical structures that the globe weavers turn on Earth.

The two spiders returned to Earth at the end of their stay in space. Esmeralda died on the return trip, after living a normal spider life. Gladys returned home, but turned out to be a boy. He was renamed Gladstone.

Turtles go around the moon

In the 1960s, before humans went to the moon, it wasn’t clear exactly how – if at all – getting close to the moon personally and closely would affect us physically. So in 1968 the Soviet space program sent two Russian tortoises (Agrionemys horsfieldii) on a journey around Earth’s companion.

Actually it wasn’t just turtles. Included in the flight were wine flies, mealworms, seeds, plants, algae and bacteria. There was also a dummy with radiation sensors, as none of the living organisms on board were distantly analogous to humans. According to a 1969 report, turtles appear to have been chosen because they are relatively easy to tie up.

The two unnamed reptilian cosmonauts were placed aboard the Zond-5 spacecraft on September 2, 1968, after which they were no longer fed. They were launched into space on September 15, 1968 and returned to Earth (in the Indian Ocean) on September 21. They finally returned to Moscow on October 7.

Their journey included seven days of space flights, several days in tropical climates (including bobbing in the ocean while waiting to be picked up), and transport back to Russia. In the end, they spent 39 days without food. Everyone would try.

Control turtles that remained on Earth were also not fed during the same period. A comparison of the two sets of turtles revealed that any changes in the space-faring reptiles were mostly the result of starvation, with a small contribution from spaceflight-related atrophy.

We’d say no one ever sent turtles to space again, but unfortunately two more turtle missions took place. Zond 7 turtles transported in 1969. In 1975, the Soyuz 20 spacecraft drove a turtle around for 90 days. And two turtles flew on the Salyut-5 space station in 1976.

Moon Trees

Just as we once did not know how space would affect animals, so we were also unaware of the effects on plants. So when the Apollo 14 mission took off on January 31, 1971, the payload contained something that we might now find a little odd: about 500 seeds.

Scientists at the US Forest Service wanted to know if tree seeds flown in microgravity and exposed to space radiation would germinate, grow, and look like seeds that never left Earth.

Five tree species were included in the bush: loblolly pine (Pinus taeda), Redwood (Sequoia sempervirens), American sycamore (Platanus occidentalis), Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), and American sweet gum (Liquidambar styraciflua). They accompanied command module pilot Stuart Roosa in 34 orbits from the moon before returning to Earth.

The seeds were then planted and cared for, and most of them survived to grow into saplings, in addition to controls that never left the earth. Now it is not surprising to us that there was no discernible difference between the two.

By 1975, the Moon Trees, as they had come to be known, were large enough to be transplanted and shipped all over America. According to this NASA website, fewer than 100 Moon Trees can be accounted for today, of which only 57 were alive when the page was compiled.

That means there could be potentially hundreds of Moon Trees hidden in the US, a lost relic from a time when our curiosity sent tiny seeds across space. And we like that.