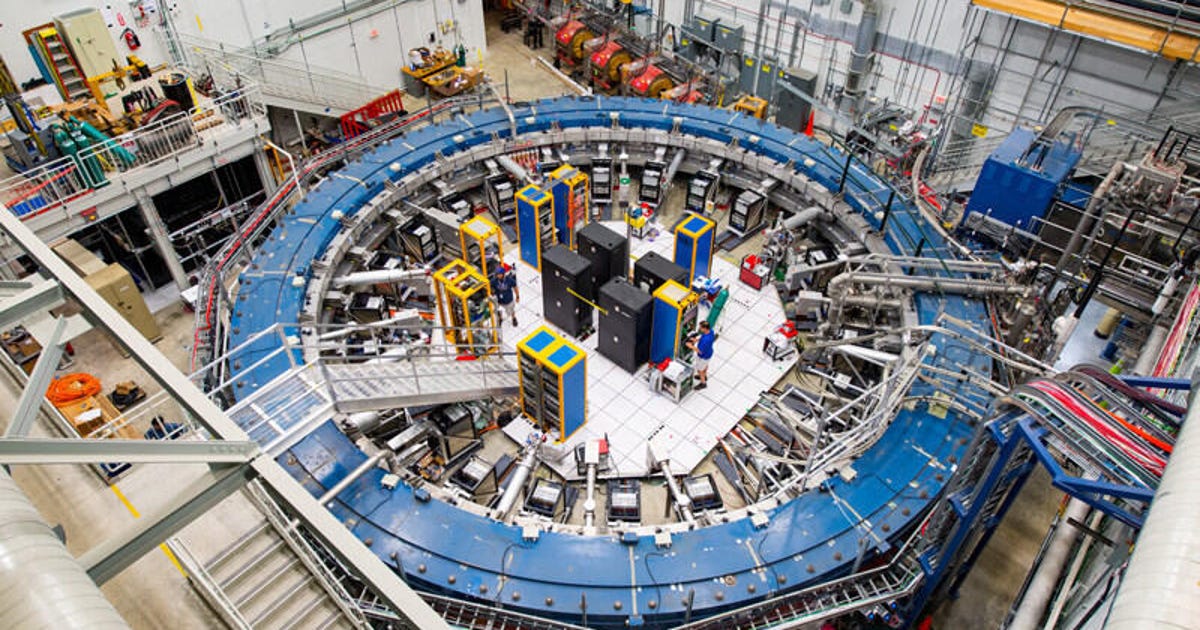

The Muon g-2 ring is located in its detector hall amid electronics racks, the muon beamline, and other equipment. Operating at minus 450 degrees Fahrenheit, this experiment studies the precession (or wobble) of muons as they travel through the magnetic field.

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory

When you activate the Large Hadron Collider and use its supreme power worldwide to destroy a number of ordinary particles at once, you can’t just create a mind-boggling 13 tera-electron-volt impact force. You may also discover that you have produced a subatomic particle whose strange wobbling could violate the laws of physics altogether.

It’s called a muon. And on Wednesday, researchers at the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory sent shockwaves through the world of particle physics when they discovered that this humble speck of a quantum curious existence could illuminate the fabric of the universe in a way we haven’t seen since the discovery of the Higgs boson almost ten years ago.

The magnet-like muons are 207 times larger than electrons and decay radioactively in 2.2 millionths of a second, making them unlikely candidates for an explosive physics discovery, according to a lavishly reported New York Times story on Wednesday. In the Standard Model of particle physics, which explains how the elementary particles of the universe interact, we have very rigorous calculations about how muons should move.

But during experiments in the Fermi Lab, researchers saw the muons wobble strangely. So strange that the wobble routinely defies the world’s most hyper-specific measurements and goes against the Standard Model. They seem to be influenced by what physicists say could be forces beyond the current known forces.

“This amount we measure reflects the muon’s interactions with everything else in the universe,” said Renee Fatemi, a physicist at the University of Kentucky, in a press release. “This is strong evidence that the muon is sensitive to something not in our best theory.”

In quantum physics, one theory holds that particles can appear suddenly and affect an item with which they interact before disappearing again. Researchers working on muons say the small variations in the wobble of the muons can be attributed to the influence of a potential host of these “virtual particles.”

While the findings follow in the footsteps of similar experiments in 2013 and 2018, the latest results need to be vetted even more. The researchers note that the odds that the muon’s wobble is a statistical fluke is about one in 40,000 – which, in science, equates to a confidence level of “4.1 sigma”. Physicists are usually not satisfied until the confidence level reaches 5 sigma.

In the meantime, however, you can find out more about the stunning muons by checking out Fermilab’s regular folk-friendly video explainer.

Read more: CERN wants to build a new $ 23 billion super-collider that is 100 kilometers long