The European Central Bank emulates its Asia-Pacific competitors by controlling government borrowing costs in a uniquely European way.

The ECB buys bonds to compensate for differences between yields for the strongest and weakest economies in the eurozoneAccording to officials familiar with the case, one person says the central bank has specific ideas about which spreads are appropriate. A spokesman for the ECB declined to comment.

Investors have long wondered if the central bank has specific levels in mind when trying to curb bond yields. The most recent insights into its strategy shed light on how policymakers are dealing with the complexity of the eurozone that makes public targeting on bond levels difficult.

Government bond yields are key to fighting the pandemic crisis. Not only do they affect all other loan costs, but keeping government borrowing affordable has become a critical part of monetary policy as businesses and workers depend on massive debt-funded fiscal support.

The ECB’s strategy explains why the spread between Italian and German debt has remained remarkably stable despite the fact that the Italian government was on the verge of collapse after the central bank accelerated the pace of bond purchases. prices According to Tanvir Sandhu, chief global derivatives strategist at Bloomberg Intelligence, the volatility is at record lows.

It is different from the so-called yield curve control applied by the Bank of Japan and Reserve Bank of Australia, which have publicly announced numerical targets for specific returns. In the case of the BOJ, it aims to be around zero per cent on the 10-year Treasury bond – although there is speculation that the bond could be broadened.

ECB President Christine Lagarde, who convenes the first policy meeting of the year on Thursday, does not have that luxury. It has to meet the monetary needs of a currency union with 19 countries, each issuing its own debt.

At the moment, that means promising to lock the financial conditions during the crisis. Those terms are broadly defined, including “all private and public sectors of the economy, both interest rates and credit volumes and terms,” the December policy meeting report said.

While that strategy is similar to controlling the yield curve, “they call it something else,” said Christoph Rieger, head of fixed income strategy at Commerzbank AG. “I feel like this is important to the ECB, they are looking at it and they are actually jealous of the BOJ. They would love to have something like that. “

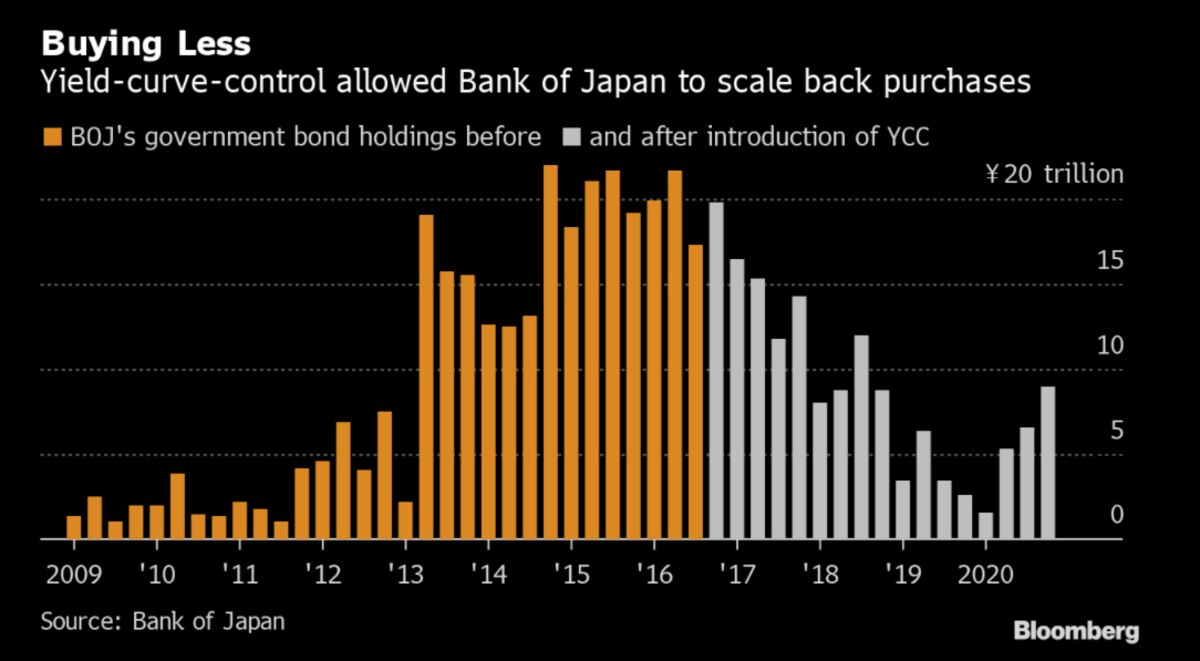

Yield curve control took hold as central banks went deeper into their toolkits after cutting interest rates to record lows and freeing up trillions of dollars when buying bonds. In theory, it’s cheaper than quantitative easing alone, as investors are essentially told not to fight back.

The BOJ adopted the policy in 2016 as an incentive tool to increase inflation. The RBA decided last March to keep the three-year rate at around 0.25% and cut that to around 0.1% in November. US Federal Reserve Vice Chairman Richard Clarida said it is part of the toolbox late last year.

Buy less

Yield curve control allowed the Bank of Japan to reduce its purchases

Source: Bank of Japan

However, the promise must be credible. Investors must believe that the central bank will spend as much as it takes to defend its policies, which is where the ECB gets into trouble.

For starters, it lacks a single binding to aim. That will soon change when the European Union starts issuing joint debt to finance its € 750 billion ($ 909 billion) recovery fund, but that plan is a temporary plan linked to the pandemic – the ECB could no longer be able to issue bonds to buy.

The central bank is also prohibited under EU law from directly financing governments. It has kept its bond buying programs legal by putting limits on what it can buy and for how long, but its control over the yield curve is implicitly limitless.

“There are a number of issues in choosing such a strategy or adding it to the ECB’s toolbox,” said Katharina Utermoehl, an economist at Allianz SE. “This could give rise to the idea that the ECB is in fact doing monetary financing.”

Read More: A QuickTake on US Yield Curve Control

The central bank has not dismissed control of the yield curve, and the Governor of the Bank of Spain, Pablo Hernandez de Cos, said this month that it is an “option worth exploring.”

Hernandez de Cos suggested targeting a technical measure, the region’s overnight index swap curve. Economists, including Nick Kounis from ABN Amro, have suggested using an average eurozone bond yield weighted by national gross domestic product.

Both Hernandez de Cos and Isabel Schnabel, a member of the Board of Directors, say the Board has never discussed formal control of the yield curve.

The measure carries broader risks, such as encouraging reckless tax policies by relieving governments of some market restrictions.

The Fed and the US Treasury agreed in 1942 to limit borrowing costs to fund the country’s participation in World War II. Five years later, inflation was in double digits amid the post-war boom and the central bank was forced to withdraw.

Explicit revenue goals also make it challenging to get out of the policy. Investors are likely to ditch bonds, which pushes up borrowing costs once they see that the target is about to expire.

Ultimately, that could mean that the ECB is ahead of what Lagarde has described as a “holistic” approach to maintaining favorable funding conditions.

“It’s not as explicit as the Japanese do, but broader,” says Florian Hense, European economist at Berenberg. “Once it is known that you explicitly control the yield curve, this commitment can be very expensive.”

– With help from Jill Ward, Masaki Kondo, Toru Fujioka and Catherine Bosley

(Updates with speculation on BOJ yield target in sixth paragraph)