NASA’s InSight mission has finally looked into Mars – and discovered that the planet’s crust can be made up of three layers. This is the first time that scientists have directly examined the inside of a planet other than Earth, and will help researchers unravel how Mars formed and evolved over time.

Before this mission, researchers had only measured the internal structures of the Earth and the Moon. “This information has so far been missing from Mars,” Brigitte Knapmeyer-Endrun, a seismologist at the University of Cologne in Germany, said in a pre-recorded lecture played at the virtual meeting of the American Geophysical Union on Dec. 15. She declined an interview with Nature, saying the work is being considered for publication in a peer-reviewed journal.

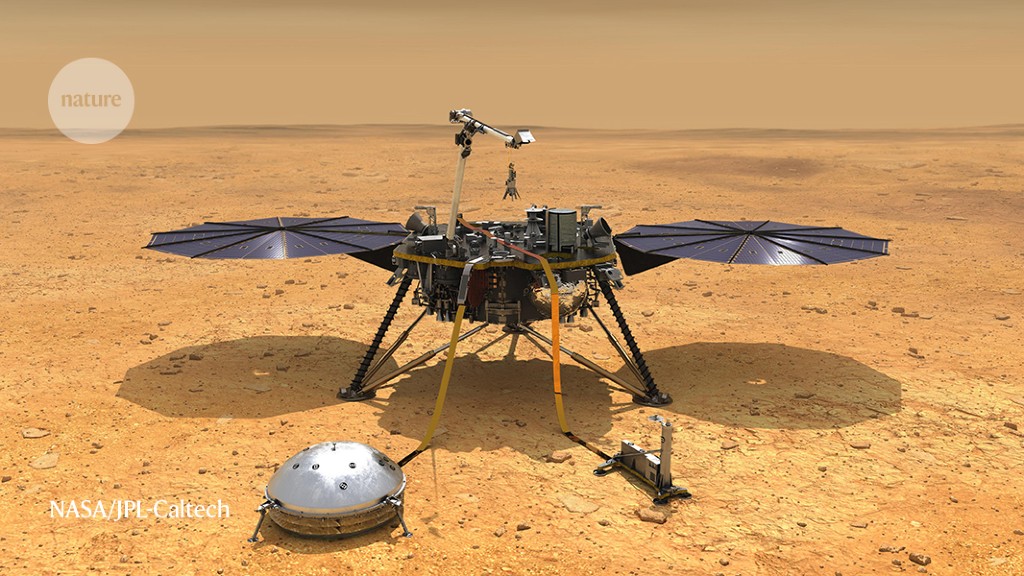

It’s an important finding for InSight, which landed on Mars in November 2018 with the aim of working out the planet’s internal structure1. The InSight lander squats near the equator of Mars, on a smooth plain known as Elysium Planitia, and uses an extraordinarily sensitive seismometer to listen for geological energy sweeping through the planet2. To date, the mission has discovered more than 480 “ marsquakes, ” said Bruce Banerdt, the mission’s lead investigator and a scientist at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. Mars is less seismically active than Earth, but more than the Moon.

As with earthquakes on Earth, seismologists use Marsquakes to map the internal structure of the red planet. Seismic energy travels through the ground in two types of waves; By measuring the differences in how those waves move, researchers can calculate where the planet’s core, mantle, and crust begin and end, and the general composition of each. Those basic geological layers show how the planet cooled and formed billions of years ago at the fiery birth of the solar system. Now “we have enough data to answer some of these big questions,” Banerdt says.

The continental crust of the Earth is generally divided into layers of different types of rocks. Researchers had suspected, but weren’t sure if the Martian crust was also layered, says Justin Filiberto, a planetary geologist at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston, Texas. Now the data from InSight shows that it has two or three layers.

A three-layer crust would work best with geochemical models3 and studies of meteorites on Mars, says Julia Semprich, a planetary scientist at the Open University in Milton Keynes, UK.

Depending on whether the crust actually has two or three layers, it is 20 or 23 kilometers thick, Knapmeyer-Endrun said during her talk. That thickness likely varies in different locations on the planet, but probably won’t exceed an average of 70 kilometers, she added. On Earth, the thickness of the Earth’s crust varies from about 5 to 10 kilometers below the oceans to about 40 to 50 kilometers below the continents.

In the coming months, InSight scientists plan to report measurements taken even deeper on Mars, Banerdt says – and eventually reveal information about the planet’s core and mantle.

In addition to listening for marsquakes, InSight’s other big scientific goal is to measure heat flow through the Martian soil using a probe called the mole. It was meant to bury itself deep in the ground, but has struggled with that – even popping out of the ground at one point. The mole has finally managed to get itself several inches deep, Banerdt says, and will try to dig one last time in the coming weeks before giving up. “We are now in what we consider to be the end game,” he says.