“This study reveals detailed patterns of extremely important infectious diseases, over a very long period of time – much longer than any human life,” said lead study author David Earn, a professor of mathematics at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario.

The smallpox story is a sobering reminder of a not-too-distant reality: the months-long wait for the accelerated Covid-19 vaccine pales in comparison to centuries when smallpox has been rampant.

“Smallpox was … staggering compared to what we’re talking about now. I mean, there’s just no comparison between the degree of devastation and fear that this disease caused,” he said.

With the help of his colleagues and undergraduate research assistants, Earn – over the past few years – digitized 13,000 weekly smallpox mortality data.

“I looked at annual smallpox counts, but not these weekly counts, and the weekly counts reveal the full structure of the epidemics, how quickly each epidemic started,” Earn said. “The shape of the epidemic curve was completely hidden before that.”

Hundreds of years of data

The new study follows research Earn has published on the historical spread of diseases such as bubonic plague, cholera and scarlet fever.

His team’s goal was to make this data public and allow scientists to analyze how disease patterns spread in populations. Many historical trends can change the spread of disease. Natural forces, such as the weather or the changing of the seasons, can cause an outbreak.

And then there are the social factors: population density, population structure, the introduction of schools and the course of wars.

The data covers 267 years, from 1664 to 1930, the last year in which there was more than one smallpox death in one week. London’s last death from disease occurred in 1934.

The researchers were particularly interested in the seasonality of smallpox outbreaks. In the 17th century, the team found, epidemics mostly occurred in the summer or early fall. But by the 18th century, those outbreaks shifted to appear in late fall or early winter.

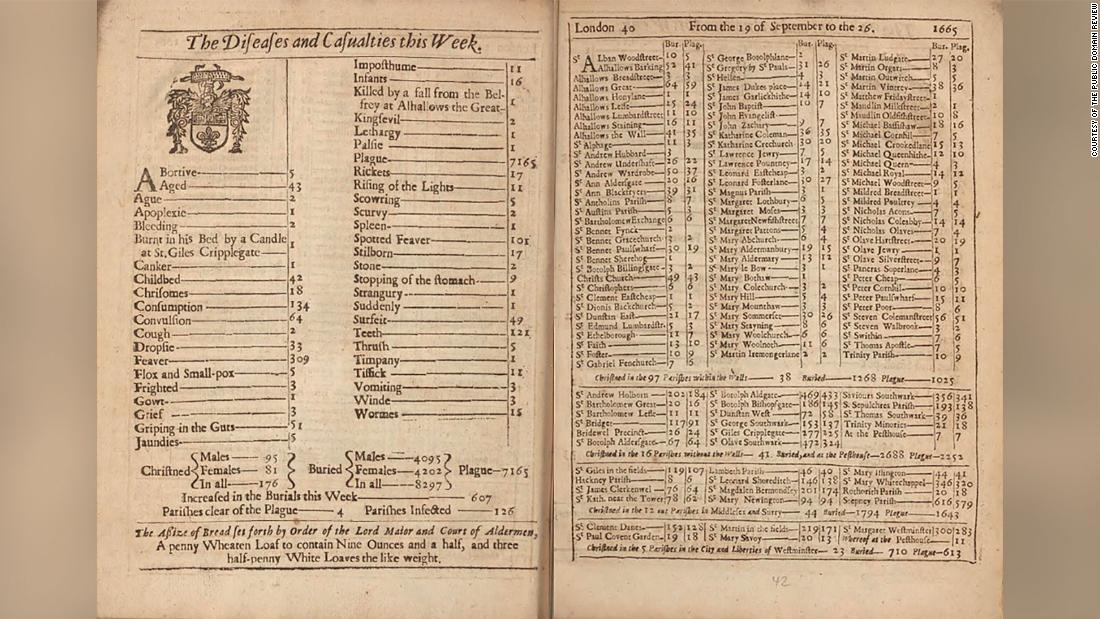

Even a cursory glance at the 17th-century archives is a window into another era, where other causes of death are “worms,” ”jaundice,” “spleen,” “lethargy,” and “scared.” For example, a page dated September 1665 lists “teeth” as one of the other leading causes of death behind the bubonic plague.

One death that week fell into the curiously specific category for “burned in his bed by a candle at St. Giles Cripplegate.”

Weekly death rates were published for only a few cities. The researchers analyzed London mortality data, which was compiled from the burial records of the Anglican Church.

While that data doesn’t capture every death in London – they could have missed fatalities that occurred outside of town or without a church funeral – the data does give a fairly accurate account of the rise and fall of smallpox over the years.

For deaths from 1842 onwards, the researchers used the Registrar General’s Weekly Return statistics for more thorough accounting.

During the 18th century, the best way to protect against smallpox was vaccination, a process in which a doctor introduced smallpox pustules, perhaps from the scab of a smallpox patient, into a person’s skin.

In 1796, the English physician and scientist Edward Jenner invented the smallpox vaccine. Actual vaccination of the entire population was another prospect, however, and epidemics would periodically peak in London for much of the 19th century.

The disease was widespread in South America, Africa, and Asia, even in the mid-20th century, prompting the World Health Organization to launch a plan to rid the world of smallpox in 1959.

Implications for Covid-19

“This research is interesting in the light of the pandemic, but it was not motivated by it,” he said, noting that the study demonstrated the importance of public health surveillance for all diseases.

“We are now gaining insight into disease transmission patterns thanks to the City of London’s systematic registration over hundreds of years,” he continued.

This new wealth of data could be useful for future researchers to understand how to address the spread of a range of diseases. That’s one more reason to remain vigilant, especially as new outbreaks can develop even after the advent of a vaccine.

“The smallpox vaccine actually prevented transmission, which is crucial to actually eradicating it,” Earn explains. “We don’t know yet to what extent that will apply to these (Covid-19) vaccines that have already been marketed.”

While Covid-19 vaccines have been shown to be effective in creating immunity to the new coronavirus, scientists don’t yet know if it’s still possible to spread Covid-19 after you get your injection.

There simply haven’t been studies to look at that problem yet, noted CNN Medical Analyst Dr. Leana Wen in an earlier interview.

By the second half of 2021, social distance, quarantines and masks may become less important. However, the history of smallpox and many of the historical outbreaks Earn has studied show that Covid-19 can certainly linger, ebb and flow for the foreseeable future.

“We could see patterns of recurrent epidemics, as we see for smallpox over this incredibly long period,” he said.

CNN’s Faye Chiu contributed to this story.