The veil between dream world and reality may be thinner than we thought. In a new study Released Thursday, scientists in four countries say they have shown it is possible to communicate with people while lucid dreaming. At least some of the time, the dreamers were said to have been able to answer yes-no questions and answer simple math problems through facial and eye movements; after that some remembered hearing the questions during their dream.

Cognitive neuroscientist and study author Ken Paller and his colleagues at Northwestern University in Chicago have been studying the link between sleep and memory for years. Sleep is generally believed to be critical to the robust storage of memories created throughout the day. But little is known about this process and how dreams can play a role in it.

“We research dreams to learn more about why dreams happen and how they can be helpful for mental functioning during awakening,” Paller told Gizmodo in an email. “As in our other work, we hypothesize that sleep knowledge events may be beneficial for memory function.”

One of the reasons dreams are difficult to understand is that most of us have a hard time remembering our dreams completely when we wake up, let alone telling them to others. But Paller and his team have been experimenting with trying to communicate with sleepers for years. Their previous research has demonstrated that people can be influenced by sounds from the outside world while sleeping. Other research on lucid dreamers – people who claim to have control over their dreams – has suggested that they can send a signal to outside observers through eye movements while dreaming (in 2018, a study suggested that these eye movements can be used to see when a person has entered a state of lucid dreaming).

Many people are familiar with one-way communication with a sleeping person, such as sleepwalking and sleeping talking are common phenomenamena But Paller’s team reasoned it should be possible to have two-way communication between dreamers and awake observers and that the dreamers should be able to remember them conversationsThey also theorized that this communication could be induced and replicated under the right conditions in the lab, which would be great for future sleep research As it turns out, they weren’t the only scientists who had this idea. At least three other research groups in France, Germany and the Netherlands pursued the same goal.

G / O Media can receive a commission

“The research groups conducted independent research and afterwards we discovered that we had conducted similar studies in different countries. Then we decided to publish all of our results together – collaboratively rather than competitively, ”said Paller.

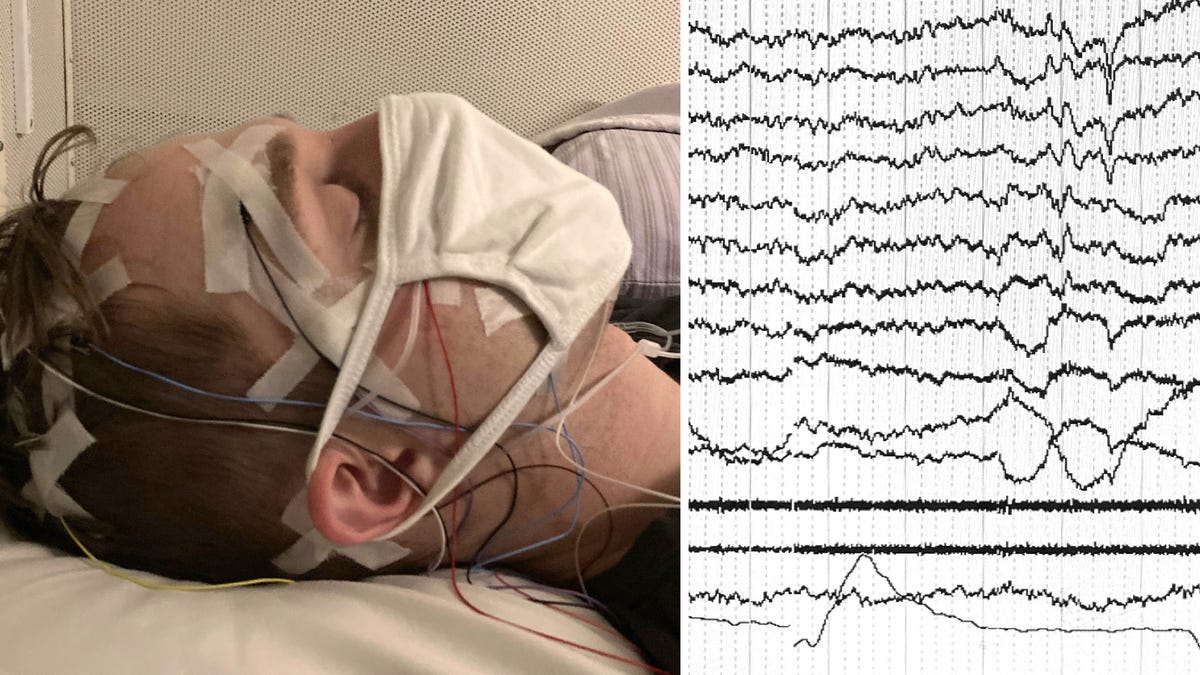

A total of 36 volunteers were involved in the study. Some were self-proclaimed experts in lucid dreams, most notably a 20-year-old French participant with narcolepsy who made it possible for them to achieve REM sleep (the sleep phase in which dreams occur most often) within the first minute of a 20-year-old. minute nap. Other participants had no previous experience with lucid dreaming, but Paller’s team tried to train all of their subjects to start a lucid dream when they heard a certain sound playing while they were sleeping. Some teams used spoken words or tones to communicate; others relied on flashing lights or lightly touching the sleepers. The volunteers were also monitored by typical sleep measurements such as EEG, which records brain activity.

In 57 sleep sessions, the participants were able to indicate that they were entering a lucid dream by eye movements 26% of the time. In these successful sessions, the scientists were able to get at least one correct answer to a question through dreamer’s eye movements or facial distortions of nearly half the time. Overall, of the 158 times they attempted to communicate with a lucid dreamer during these sessions, they got a correct response rate of 18% (the most common response, about 60%, was no response).

When the volunteers were asked about their experiences, some said they could remember the pre-dream instructions they were given and tried to carry them out. Some also said that they had heard the questions they received in the dream, although not always in the same way. Some reported hearing words that clearly felt as if they came from outside of their current reality, while others said it felt as if they were hearing them through a radio or some other form of communication within the dream. But there were still times when people couldn’t clearly remember what had happened or when the questions they said they got in the dream didn’t match the questions they actually got.

The study findings, published in Current Biology, are based on a small sample size, so the conclusions should be viewed with some extra caution. But they do show that it is at least possible to have two-way communication with dreamers, Paller said. And the fact that different groups of scientists, in different parts of the world and using slightly different methods, were all able to capture this event indicates that it is not just an isolated or misidentified phenomenon, he added. to.

The team came up with the phenomenon of ‘interactive dreaming’. And now that they feel they have shown that it is possible, they intend to keep improving people’s ability to enter that state.

“We are currently looking into ways to have running experiences in people’s homes instead of in the sleep lab. This can be beneficial as people are not affected by the unusual environment of a sleep lab or the monitoring technology we use, ”said Paller. One way they explore for future research is to use a smartphone app that teaches people how to lucid dream and get better at it – an app that already available, for all the curious spectators out there.

The hope is that this technique will allow researchers like Paller to get a little closer to unraveling the mysteries of our dream lives and how they can affect our waking hours. Over time, this research can even be applied proactively to improve people’s lives by improving their sleeping and dreaming habits.

“The applications could be developed for problem solving, practicing well-honed skills, spiritual development, nightmare therapy, and strategies for other psychological benefits,” Paller said.