Twenty million years ago, the coasts of northern Taiwan were sandstone sediments on the seabed, where 6-foot-long worms lurked in their burrows, waiting for unsuspecting prey to pile up.d. Now a team of geoscientists has recorded 319 trace fossils of those carnivorous sea worms whose burrows are fossilized in the Miocene mud.

“In the beginning, we were firmly convinced that it was a very fancy shrimp hole,” Ludvig Löwemark, a sedimentologist at National Taiwan University, said in a video conversation. And then, after talking to a few other experts, we leaned toward this bivalve hypothesis. But eventually we became increasingly convinced that it is actually a bobbit worm that made this trail. “

Trace fossils are remnants of the creatures who created them – footprints and other hardened remnants of the animals’ movements in life, rather than the fossil remains of the critters themselves. The worms the researchers suggest once lived in these burrows have long since disappeared, presumably consisting of soft tissues that deteriorated shortly after death. An analysis of the fossils is published today in the journal Scientific Reports.

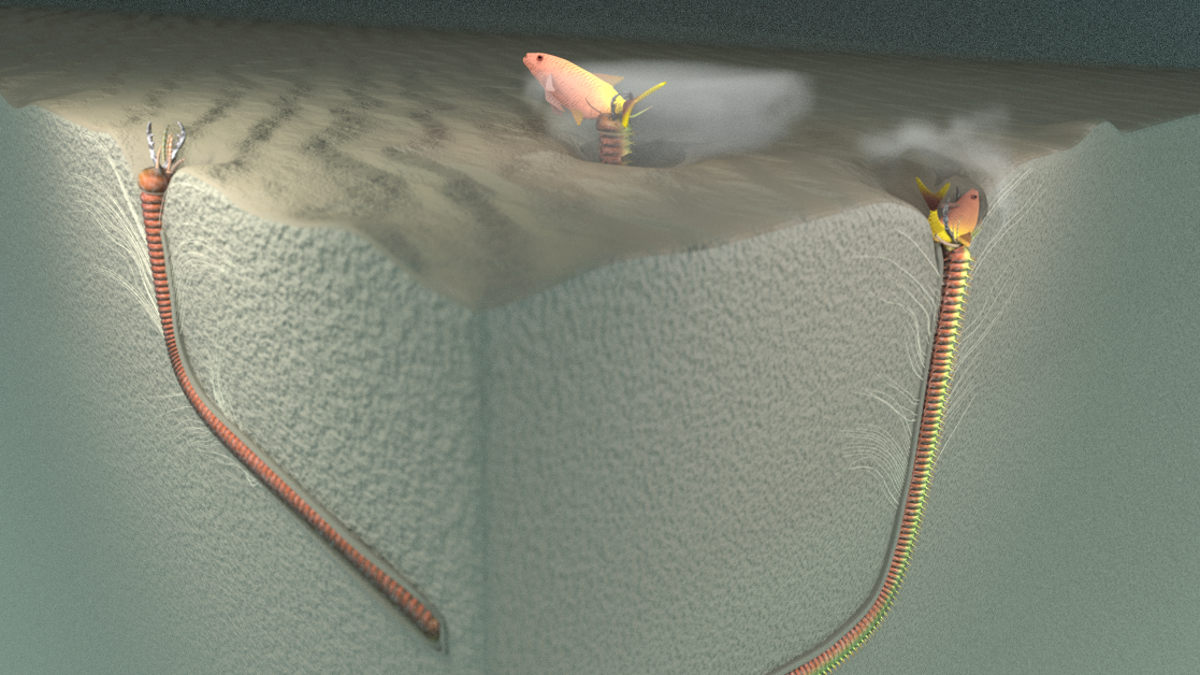

Löwemark’s team, led by Yu-Yen Pan of National Taiwan University, discovered hundreds of pockmarks littering Taiwan’s rocky coastline. They found that the holes swung horizontally as they went deeper, forming a boomerang-shaped hollow about an inch wide and six feet deep. The tapered bend of the cave suggested to the team that at a certain depth, the earth beneath the creature became more difficult to dig through or became more anoxic. (Worms breathe through their skin, so if the soil they are immersed in doesn’t have enough oxygen, it can be deadly).

G / O Media can receive a commission

Where the burrows led out to the then seafloor, there was a ‘feathering’ pattern the team identified, suggesting that the silty seafloor had collapsed in a funnel shape around the structure, indicating a vacuum left behind by a creature calling itself withdraws its hole. They concluded that the animals that created the burrows are close relatives of today’s deadly Bobbit worms, which still grow up to 3 meters in length and are named after an infamous 90s criminal case involving a cut penis (although it may be time to change that name). The trace fossils in Taiwan are mentioned Pennichnus beautiful!, meaning ‘beautiful feather track’, the latter name being derived from the Portuguese name for Taiwan, Formosa.

“It really doesn’t matter who created it – it’s the shape and function of the trace fossil that gets a name,” Löwemark said. “So you have a gender for similar traits, fossils that have been produced in a specific way, because of feeding behavior or locomotion or whatever … and then you have a generic name.”

After the other culprits were eliminated, the shrimp would have left ‘inverting’ offshoot chambers in their burrows, while the worms are more of a one-way operation and a bivalve suspect at the end of the burrow marker where he gave way to his shell – a predatory ambush worm appeared in fit the profile. Today, the bobbit worm hunts by feel: when it senses a disturbance outside its burrow, the worm attacks the as yet unidentified organism at lightning speed, armed with hardened shears. When properly secured, the worm snatches the prey into its hole, and the sand falls over the entrance, hiding the gruesome scene. If you blinked, you’d never know it happened.

“It is a very cruel procedure,” explains Löwemark.

When you think about it on a grand scale – the team found hundreds of these burrows in two locations along the coast – it sounds like a terrifying reverse game of whack-a-mole.