Astronomers have confirmed the existence of a three-star exoplanet 1,800 light-years from Earth. Planets parked in multi-star systems are rare, but this object is particularly unusual due to its inexplicably strange orbital alignment.

The first trace of KOI-5Ab was spotted by NASA’s Kepler space telescope in 2009, but that was very early in the mission, so the exoplanetary candidate was set aside. in favor of easier goals. Not a terrible decision, given that over the course of his illustrious nine-year career, Kepler saw 4,760 exoplanet candidatess, about half of which has yet to be confirmed.

“KOI-5Ab was abandoned because it was complicated and we had thousands of candidates,” explains David Ciardi, NASA’s Exoplanet Science Institute chief scientist in a NASA. statement. “It was easier to pick than KOI-5Ab, and we learned something new every day from Kepler, so KOI-5 was largely forgotten.”

Ciardi, along with his colleagues, have now taken a fresh look at KOI-5Ab, namely NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite and several ground-based telescopes, including the Keck Observatory in Hawai’i. The team was finally able to confirm KOI-5Ab as a bona fide exoplanet, and in the process discovered some fascinating – if not completely confusing – aspects of its stellar environment. Ciardi, a research astronomer at Caltech, recently presented his team’s findings at a virtual meeting of the American Astronomical Society.

G / O Media can receive a commission

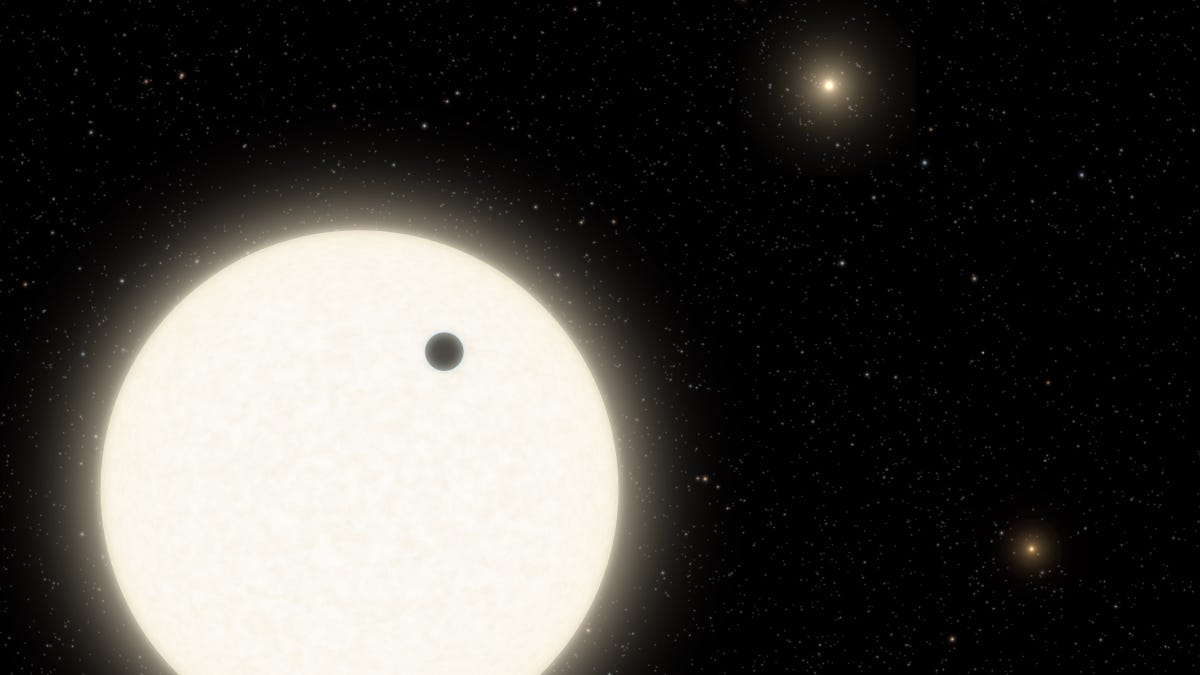

The confirmation of KOI-5Ab was done with the proven transit method, in which an orbiting planet passes in front of its star from our perspective, causing a short dimmer. The confirmation was further validated by another technique, the wobble method, in which the light gravity of a planet orbiting the Earth creates a detectable shock in its host star. TESS was used for the throughput method, while Keck was used to detect the wobble. The combined data allowed the researchers to rule out other possibilities, such as a fourth star.

KOI-5Ab is probably a gas giant, similar to Neptune in terms of size. It’s in a triple star system, and while its orbit is a bit strange, its overall environment is less chaotic than it might sound.

Despite having three stellar companions, KOI-5Ab orbits a single star, KOI-5A, once every five days. This guest star is trapped in common orbit with a nearby star named KOI-5B, and the two orbit each other once every 30 years. KOI-5C, a more distant star, orbits this pair once every 400 years.

The problem is related to the orbital alignment of KOI-5Ab to KOI-5B. The two objects do not share the same orbital plane, which is an unexpected result – a result that calls into question conventional planetary formation theories, such as how such objects are thought to be form of a single protostellar disk.

“We don’t know many planets that exist in triple star systems, and this one is extra special because its orbit is skewed,” said Ciardi. “We still have many questions about how and when planets can form in multi-star systems and how their properties relate to planets in single-star systems. By studying this system in more detail, we may be able to gain insight into how the universe makes planets. “

Ciardi and his colleagues don’t know the reason for the misalignment, but their working theory is that during the development of the system, KOI-5B shrugged, disrupting the path of KOI-5Ba and migrating it inward to its host star.

According to NASA, about 10% of all galaxies comprise three stars. Planets have been spotted in triple star systems before, and also within binary star systems, but such discoveries remain rare. Multiple galaxies, it seems, do not tend to house many planets. This could mean that the conditions for planet formation in these environments are not ideal, but it could be the result of an observational selection effect, in the sense that it may be more difficult for astronomers to see planets in multiple galaxies compared to star systems.

The answer to this question is important, as it has serious implications for the quest for alien life. Multiple star systems are good for more than 85% of all galaxies in the Milky Way Galaxy. If we confirm that multi-star systems tend to have far fewer planets, and as a result fewer life-bearing planets, astrobiologists and SETI scientists should turn their attention to single-star systems.

This list can be further reduced. As many as three quarters of all stars in the Milky Way are red dwarfs, which because of their tendency to explosion Nearby planets with solar flares could be equally bad candidates in the quest for alien life.

Given these factors, it is easy to feel that life must be exceptionally rare in the galaxy. This could very well be the case, but it is important to remember that the Milky Way has about 100 billion stars. That still leaves us a lot to choose from, which could house a handful of civilizations that ask the exact same questions as this one.