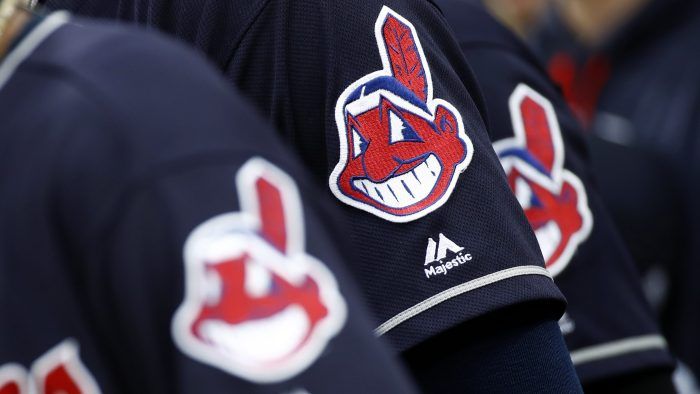

Last week, we celebrated when the Cleveland Indians decided to change the name of the baseball team starting in 2022, although it’s unclear why the team feels it necessary to wait another year before doing so.

His move underscores what many have been saying for decades: There is no significant dividing line between the blatantly racist name of the Washington football team and nicknames like the Indians, Braves and Chiefs who claim to honor the Indians. They have no excuses. All Native American pets must be eliminated.

To many sports fans, it may seem that the attack on Native American pets has suddenly emerged as the latest manifestation of the so-called “cancellation culture.” But in reality, the recent announcements from Washington, Cleveland, and many universities and high schools are the culmination of a decades-long effort by activists and academics to demonstrate the damage done by Native American cartoons in sports and entertainment. It’s been 30 years since St. John’s University abandoned its pet Red Men and 48 years since Stanford University changed its nickname from Indians.

When Native American nicknames were adopted at the beginning of the last century, the equipment owners and the journalists who chose them did not do this to honor the Native Americans. The nicknames, mascots, and accompanying cartoons were meant to be funny or intimidating, but never honorable. They implicitly associated indigenous peoples with animals. At the same time that sports teams were taking Native American nicknames, the federal government sought to eradicate Native American cultures by eliminating them or assimilating them in boarding schools. The Boston Braves (now Atlanta) are named after an owner who liked to dress up in fake Native costumes at political rallies. The name was no more intended to honor Native Americans than a Delta Tau Chi toga celebration in honor of the ancient Romans.

And even if many fans in Cleveland, Atlanta, Kansas City, and Chicago genuinely believe these nicknames are honorable and beneficial to Native Americans, the data says otherwise. The latest and greatest research indicates that people who strongly identify as Native Americans find the “ax” and headband fanatics overwhelmingly offensive. Studies by Stephanie Fryberg and others have shown the damage Native American cartoons and stereotypes do to Native youth. Native pets also harm non-natives, cultivate implicit prejudice, and continue the cycle of stereotypical thinking.

Proponents of non-overtly offensive team names also claim they play an important role in preserving the memory of indigenous culture. First, Native American culture is not a memory. Native Americans exercise their sovereignty in the United States, deal with environmental damage, break into mainstream media, and reinvent traditional cultural practices, just to name a few. They have acquired roles in business, government, technology, academics and sports. They exist in Reservations and in the main cities. The fundamental problem with Native American pets is that they hide all the success and diversity of the Indian land behind stereotypes of fierce naked warriors. Not to mention the total elimination of Native American women, prominent matriarchs who lead their communities and tribes.

The native mascot is so ubiquitous that aside from Pocahontas or Sitting Bull, we can hardly believe that people know any other reference to Native Americans. Pets won’t change that. We trust that no one who saw the Kansas City Chiefs last weekend will see the arrowheads on their helmets and think, “I wonder if indigenous communities face unique challenges with the coronavirus.” Or “Isn’t it great that an Indian has finally been nominated for Home Secretary?”

We are delighted that the Atlanta Braves organization has partnered with Indigenous communities, and it is great to see the Chicago Blackhawks appreciate Native American land at the start of their home games. But we wonder why not all teams do the same. It’s not that the New York Jets are the only team to honor the military.

Does it really benefit the indigenous community? Or is it to gain public permission and approval for his ongoing dehumanization of a whole group of people? Connecting with and employing modern Indians should be a goal for all professional sports franchises, not just those with an embarrassing history of cartoons and stereotypes.

Cleveland has recognized that it is time for a change. We hope others will follow soon.