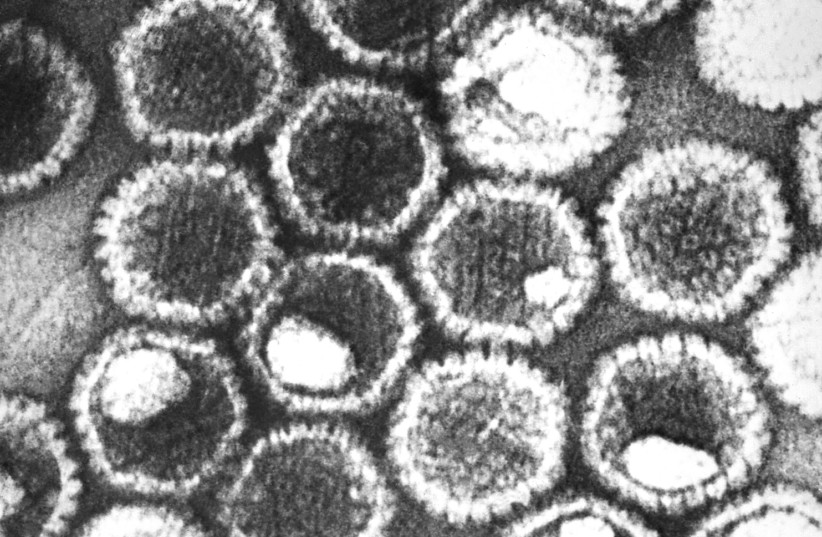

A groundbreaking discovery into the causes of herpes attacks by researchers at the University of Virginia School of Medicine could provide new ways to prevent cold sores and recurring herpes-related eye conditions.

“Herpes simplex recurrence has long been associated with stress, fever and sunburn,” said researcher Anna R. Cliffe, PhD, of UVA’s Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Cancer Biology. “This study sheds light on how all of these triggers can lead to herpes simplex-associated disease.”

Cliffe and her colleagues found that when HSV-infected neurons were exposed to stimuli that induce “neuronal hyperexcitability,” the virus was able to sense the specific change and seize the opportunity to reactivate.

Working in a model developed by the Cliffe lab that looks at HSV-infected neurons in mice, the researchers determined that the virus essentially “hijacks” an important pathway for an immune response in the body.

cnxps.cmd.push (function () {cnxps ({playerId: ’36af7c51-0caf-4741-9824-2c941fc6c17b’}). render (‘4c4d856e0e6f4e3d808bbc1715e132f6’);});

if (window.location.pathname.indexOf (“656089”)! = -1) {console.log (“hedva connatix”); document.getElementsByClassName (“divConnatix”)[0].style.display = “none”;}

In response to prolonged periods of inflammation or stress, the immune system releases a specific cytokine called Interleukin 1 beta. This cytokine is also present in epithelial cells in the skin and eye and is released when these cells are damaged by ultraviolet light.

Interleukin 1 beta then increases excitability in the affected neurons, opening the stage for HSV to flare up, the UVA researchers found.

“It is truly remarkable that the virus has hijacked this pathway that is part of our body’s immune response,” Cliffe said. “It shows how some viruses have evolved to take advantage of what should be part of our infection control machines.”

The researchers argue that the discovery could lead to revolutionary new treatments in virology, although more research needs to be done before that could happen.

“A better understanding of what causes HSV to re-activate in response to a stimulus is needed to develop new therapies,” Cliffe said. “Ultimately, what we hope to do is attack the latent virus itself and make it stop responding to stimuli like Interleukin 1 beta.”