iOS 14 has added a new “BlastDoor” sandbox security system to iPhones and iPads to prevent attacks with the Messages app. Apple did not share information about the new security addition, but it was explained today by Samuel Groß, a security researcher at Google’s Project Zero, and highlighted by ZDNet.

/article-new/2020/06/messages-pinned-conversations-ios-14.jpg?resize=560%2C410&ssl=1)

Groß describes BlastDoor as a tight sandbox service responsible for parsing all untrusted data in iMessages. A sandbox is a security service that runs code separate from the operating system and it works within the Messages app.

BlastDoor views all incoming messages and inspects their content in a secure environment, which prevents malicious code in a message from interacting with iOS or accessing user data.

/article-new/2021/01/project-zero-blastdoor.jpg?resize=560%2C458&ssl=1)

/article-new/2021/01/project-zero-blastdoor.jpg?resize=560%2C458&ssl=1)

/article-new/2021/01/project-zero-blastdoor.jpg?resize=560%2C458&ssl=1)

/article-new/2021/01/project-zero-blastdoor.jpg?resize=560%2C458&ssl=1)

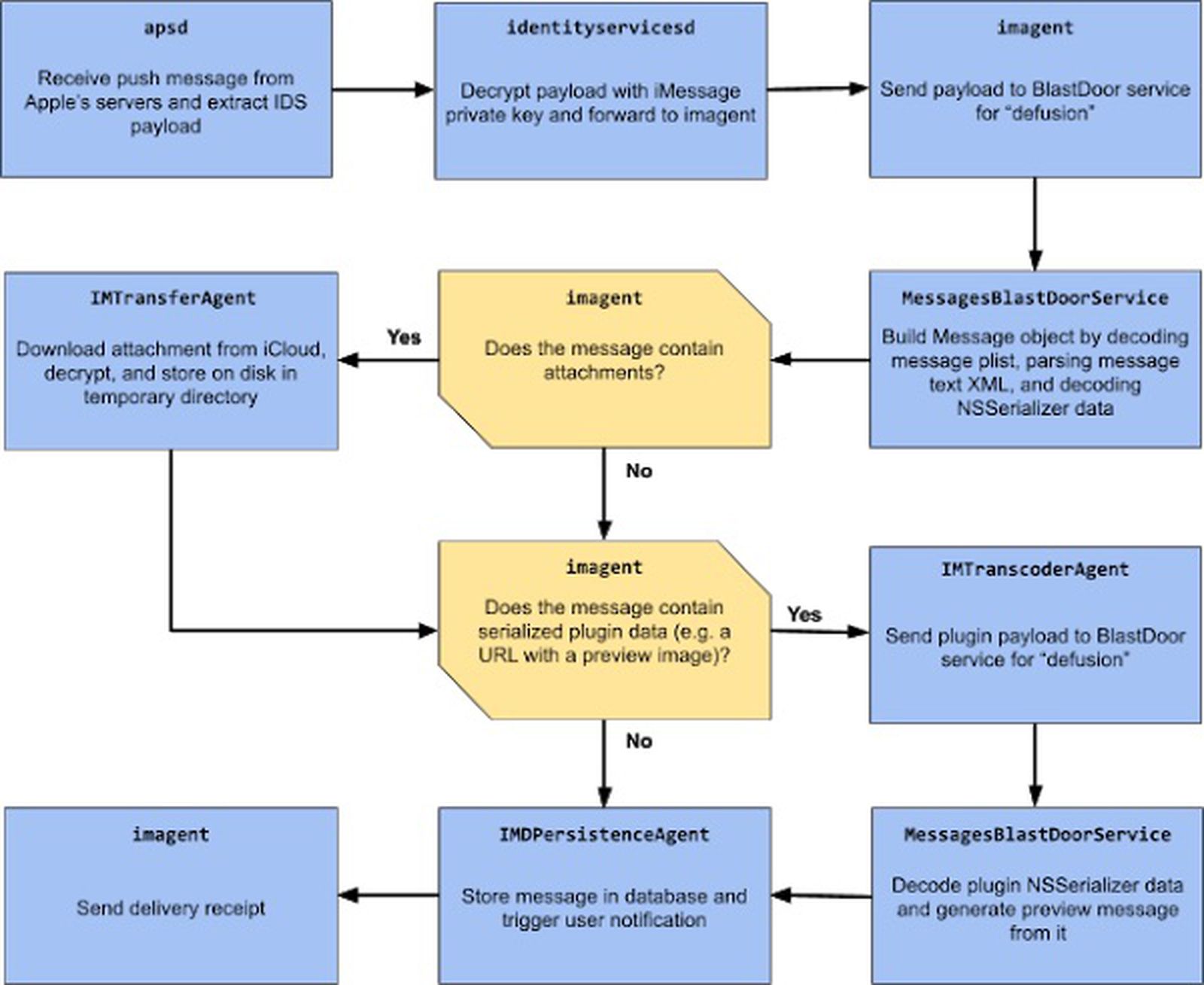

As can be seen, most of the processing of complex, untrusted data has moved to the new BlastDoor service. In addition, with its 7+ involved services, this design makes it possible to apply fine-grained sandboxing rules, for example, only the IMTransferAgent and apsd processes are required to perform network operations. As such, all services in this pipeline are now properly sandboxed (with the BlastDoor service arguably the strongest sandbox).

The feature is designed to thwart specific attack types, such as those where hackers used shared cache or brute force attacks. As ZDNet points out that in recent years security researchers have discovered bugs in remote code execution in iMessage that could infiltrate an iPhone with just text, which BlastDoor should address.

Groß discovered the new iOS 14 feature after investigating a Messages hacking campaign targeting Al Jazeera journalists. The attack did not work in “iOS 14”, and investigating why led to his discovery of BlastDoor.

According to Groß, Apple’s BlastDoor changes are “close to the best that could have been done given the need for backward compatibility” and will make the iMessage platform significantly more secure.

This blog post discussed three improvements in iniOS 14 that affect iMessage security: the BlastDoor service, moving the shared cache, and exponential throttling. Overall, these changes are probably very close to the best that could have been done given the need for backward compatibility, and they should have a significant impact on the security of iMessage and the platform as a whole.

It’s great to see Apple set aside the resources for major refactorings like this to improve end-user security. In addition, these changes also underline the value of offensive security work: not only were some bugs fixed, but instead, structural improvements were made based on insights gained from developing exploit.

Those interested in the full rundown of how BlastDoor works can visit the Project Zero blog post on this topic.