Ted Horowitz | Getty Images

One of the amazing aspects of the human response to the Covid-19 pandemic is the speed with which scientists have explored every facet of the virus to limit the loss of life and plan for a return to normalcy. At the same time, much research into non-coronavirus has virtually come to a standstill.

Because research labs and offices were closed to all but essential workers, many scientists were stuck at home, their fieldwork and meetings were canceled, and planned experiments were launched as they struggled to figure out how to keep their research programs going. Many took the opportunity to catch up on scholarship and paper writing; some – in between caring for children – devised strategic solutions to keep the scientific juices flowing.

To gauge how researchers in different fields are doing, Knowable Magazine spoke with a whole host of scientists and technical staff – including the specialists who keep genetically important fruit flies alive, the maintenance head of an astronomical observatory who keeps telescopes safe and on standby during lockdown, and a pediatrician who struggles with conducting clinical trials for a rare genetic disease. Here are a few bits of scientific life during the pandemic.

Agnieszka Czechowicz, Stanford University School of Medicine

Pediatrician Agnieszka Czechowicz, Stanford University[/ars_img]Czechowicz is a pediatrician in Stanford’s division of stem cell transplantation and regenerative medicine, where she leads a research group developing new therapies and conducting clinical studies on rare genetic diseases.

Agnieszka Czechowicz’s father is suffering from severe Parkinson’s disease. The coronavirus pandemic forced him to stay in and away from people, depriving him of the physical conditioning and social interactions he needs to deal with his illness. A recent fall left him in the hospital, further worried that he could contract Covid-19 there and further isolate him. >> For Czechowicz, his situation brought sharply into focus the challenges that the coronavirus has imposed on those conducting clinical trials. including those who run them, with patients traveling to hospitals across the country. “Would I now have him travel to a clinical site for a new Parkinson’s treatment?” she says. “Absolutely not.”

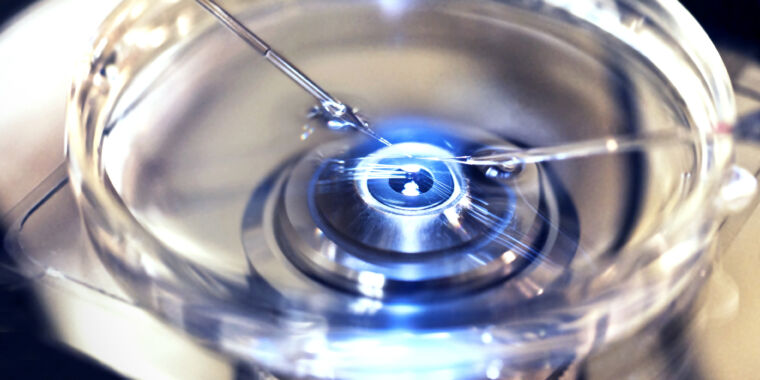

The pandemic forced Czechowicz to halt the clinical trials it oversees for a rare childhood genetic disease called Fanconi anemia, a condition that impairs the body’s ability to repair damaged DNA and often leads to bone marrow failure and cancer. The treatment that Czechowicz and colleagues are testing involves extracting blood-forming stem cells from the patient’s bone marrow, inserting a healthy copy of a missing or malfunctioning gene, and then re-injecting those cells into the patient.

“Every aspect of what I do is greatly affected by the pandemic,” said Czechowicz. One of her early-stage clinical trials involves testing the safety of the therapy. But during the initial withdrawal – which began in mid-March and lasted two months – her patients could not easily travel to Stanford for the necessary follow-up visits, and remote monitoring was difficult.

“There are special blood tests and bone marrow tests that we have to do. In particular, it is critical to get the samples to make sure the patients don’t develop leukemia, for example, ”she says. “There is no way to know without actually checking the bone marrow.” She had to overcome major hurdles to get her patients evaluated.

Another early stage study, designed to determine the effectiveness of the therapy, also had to stop enrolling new patients. Because speed is important in the treatment of Fanconi anemia – the children are likely to lose stem cells all the time – any delay in treatment can be a source of great fear to their parents. Czechowicz had to explain to them why the processes were temporarily halted. “It was really challenging to have these conversations with the families,” she says.

With the relaxation of travel and workplace restrictions, families began traveling to Stanford in June, but as infections are on the rise again, many families are becoming wary again, Czechowicz said. Fortunately, her trials are small, so she can guide any family through resuming the trials safely and continuing with the follow-up. Her own team must also follow strict safety protocols. For example, although her lab has 10 members, only two can be in the lab at a time and only one parent is allowed to enter the clinic with the child.

Not all clinical studies can pay so much attention to individual patients. Large studies involving hundreds of patients can span multiple locations and require much more monitoring, so resuming them remains difficult. Also, limitations on working with full bore are slowing down the pipeline for new therapies. “We will not see the impact of this in the coming years”, says Czechowicz.

Abolhassan Jawahery, University of Maryland, College Park

Jawahery is a particle physicist and member of LHCb, one of the main experiments at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider (LHC), the particle physics laboratory near Geneva.

In December 2018, well before the coronavirus pandemic started, the LHC was shut down for upgrades. Housed in a 17-mile (27-kilometer) tunnel some 100 meters underground, the LHC accelerates two proton beams, one clockwise and one counterclockwise, and collides them head-on at four locations. There, four gigantic underground detectors – ATLAS, CMS, LHCb and ALICE – sift through the fragments of particles created by the collisions in search of evidence of new physics. (For example, ATLAS and CMS have found the Higgs boson, the fundamental particle of the Higgs field, which gives all elementary particles their mass.) >> For the next series of experiments, which aim to analyze the properties of subatomic particles with greater precision To investigate, the LHC had to increase the intensity of its proton beams. Therefore, the four detectors also had to be upgraded to handle the resulting higher temperatures and increased radiation at the sites of the particle collisions. Work was on track for a reboot around May 2021, until the pandemic wiped out all the scientists’ careful plans.

The LHC and its four detectors are each managed by a separate partnership. CERN, which operates the LHC, hopes it can restart the collider by February 2022. “They think they can turn on the accelerator when there are no more major catastrophic events,” says physicist Abolhassan Jawahery. But the impact on the four detectors is less clear.

Before the LHCb upgrade, Jawahery’s team at the University of Maryland had worked to build approximately 4,000 extremely sensitive electronic circuit boards. These boards must be “burned in” before they can be sent to CERN. “We put them in an oven, literally cook the shelves, then run extensive tests to prepare them so we can put them on the throttle and run them for 10 to 20 years,” says Jawahery. “And none of that could be done during the close of the pandemic.”

The team resumed work in June, but with restrictions from the state of Maryland. Jawahery runs two labs and for months only two people were allowed in one lab and three in the other, making progress extremely slow. Still, his team is fortunate not to be dependent on supplies from countries badly affected by the corona virus. Other labs weren’t so lucky. For example, scientists in Milan built some electronics and detector components for the LHCb, and a lab at Syracuse University in New York has built sensors that rely on shipments from Milan. When Milan closed completely at the height of the pandemic, Syracuse also stopped working on Milan-dependent components.

For Jawahery, the lockdown had a silver lining. The most recent run of the LHC had yielded about 25 gigabytes of data per second, but his team had found little time to analyze any of it before the pandemic. “We complained that we spent all of our time building the new instrument and the data just keeps coming,” he says. When he and his team were locked out of their labs, they turned to their data backlog. “We could do real physics,” he says. “We are already getting ready to publish some papers.”