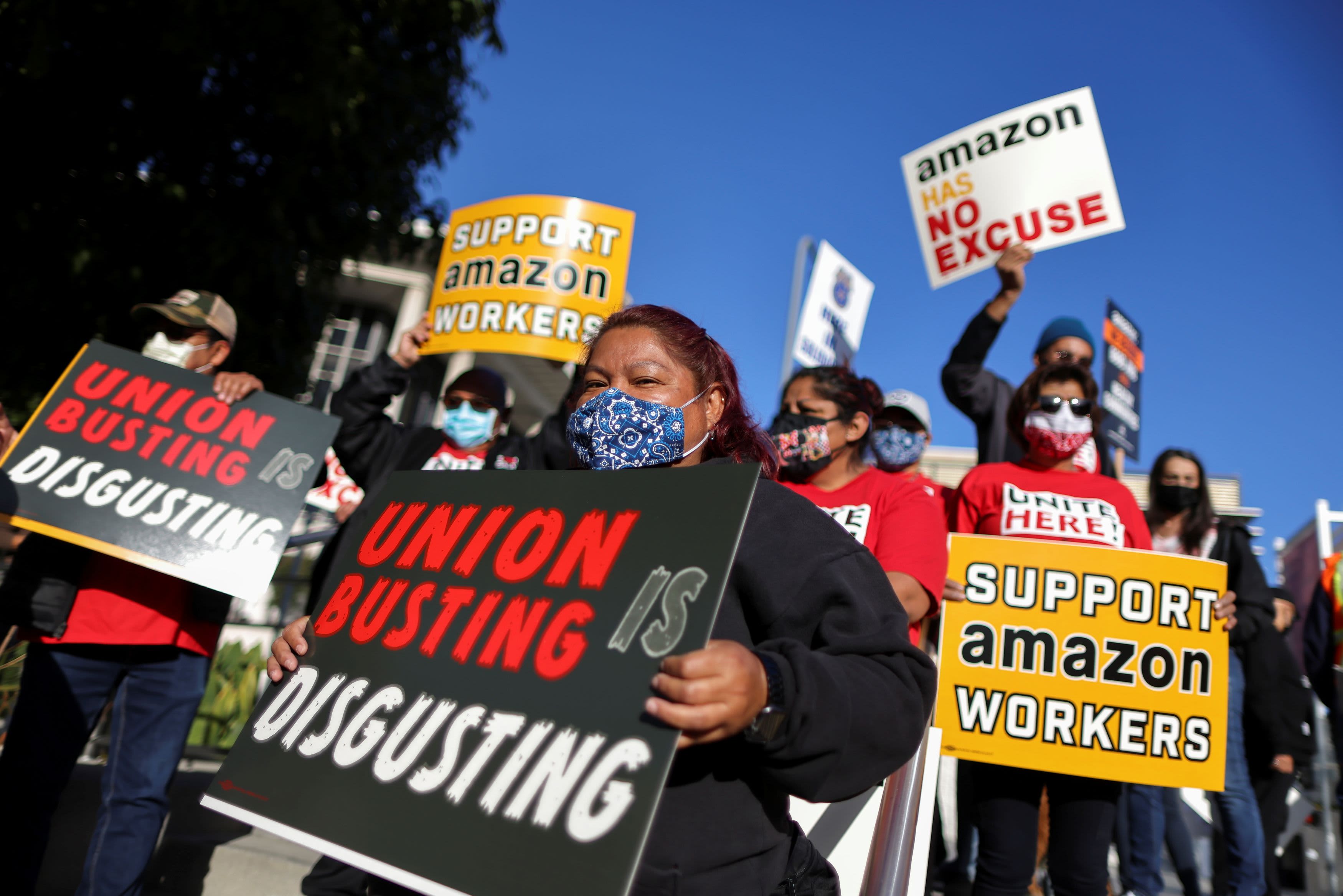

People protest in support of the Alabama Amazon workers’ union efforts in Los Angeles, California, March 22, 2021.

Lucy Nicholson | Reuters

Amazon solidly covered a union action last week at one of its Alabama warehouses, a major victory for the e-commerce giant that has long resisted unionizing efforts in its facilities.

Warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama, voted overwhelmingly to reject unionization, with less than 30% of the vote in favor. The Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union, which led the union action, plans to challenge the outcome, arguing that Amazon broke the law with some of its anti-union activities before and during the vote.

The outcome represents a setback for the organized workers, who had hoped that Bessemer’s election would help gain a foothold at Amazon. But unions, worker advocates, and some workers at the Bessemer facility, known as BHM1, said they believe the Bessemer election will fuel further attempts at organization in other warehouses across the country. Union leaders say Bessemer’s election has also revealed to the general public how far employers will go to avoid unions.

According to multiple workers and union representatives describing the tactic, Amazon launched an aggressive PR campaign on BHM1, including text messages to employees, flyers, a website urging workers to “do it without dues,” and flyers posted in bathrooms that encouraging workers. to vote “NO”. “

Amazon sent text messages and mailers urging workers at its Bessemer, Alabama factory to “vote NO”.

Amazon’s greatest opportunity to influence employees came in the form of so-called captive audience meetings, which employees had to attend while on duty. Amazon held the meetings weekly from the end of January to the beginning of February. Employees sat for about 30 minutes at PowerPoint presentations that discouraged unionization and were given the opportunity to ask questions of Amazon representatives.

Captive audience meetings are a common tactic used by employers during union campaigns. Proponents of proposed labor law reforms, such as the Protection of the Right to Organize Act (PRO) awaiting passage in the Senate, have argued that captive audience meetings serve as a forum for employers to disseminate anti-union messages’ without the union has an opportunity to respond. “The PRO law would prohibit employers from making these meetings mandatory.

Amazon said it organized ongoing meetings in small groups to let employees know all the facts about joining a union and about the election process itself.

The company also defended its response to the broader union campaign, arguing in a statement following the outcome that workers “heard far more anti-Amazon reports from the union, policymakers and media than from us.”

Why some voted ‘no’

Amazon’s coverage during the meetings was more compelling for some BHM1 employees than others.

A Bessemer employee, who started working at Amazon last year, said he felt Amazon used some scare tactics when talking to workers about the union, but also told CNBC he did not understand how the union would help workers at BHM1. This person, who asked for anonymity to avoid retaliation, said the RWDSU had not explained what they were going to do for employees and did not respond to his request for information about how they had helped employees on other job boards.

In addition to his doubts about the RWDSU, this employee said he has also had a mostly positive experience working for Amazon. While some workers complained about the stressful, demanding nature of the job, he said a previous construction job had prepared him for the physical labor of warehouse work, so he finds it easy. Amazon’s salary and benefits are also a step up from his previous job.

Ultimately, this worker voted against unionization.

In private Facebook groups where Amazon employees engage in conversation, other BHM1 employees shared their views on the union action. One employee feared that if the union were voted on, employees would lose access to certain Amazon benefits, such as its upskilling program, where Amazon pays a percentage of tuition to train warehouse workers for jobs in other high-demand areas.

Another employee thought there was no need for a union and claimed that if you work hard you can succeed at Amazon: “I voted no. Amazon is just a game, with rules. Learn the rules, play the game, go up,” win. “

Mandatory meetings

Some BHM1 employees found Amazon’s anti-union reports too aggressive.

A BHM1 employee who works as a stower, meaning items are transferred in empty storage bins throughout the facility, said Amazon designed the texts, flyers, and mandatory meetings to convey a message that the union would not help anyone. This employee requested anonymity out of concern about the loss of their job.

The worker, who voted for the union, said he was wary of showing support for unionization in front of Amazon and his colleagues, and was nervous to ask questions, instead being stupid to avoid was fired.

Aerial view of the Amazon facility where workers will vote to unite, in Bessemer, Alabama, March 5, 2021.

Dustin Chambers | Reuters

In a mandatory meeting held before the ballots were distributed in February, this employee said Amazon wanted to raise doubts about how workers ‘rights would be spent by telling workers that the RWDSU spent more than $ 100,000 a year on workers’ vehicles. . The employee was skeptical of Amazon’s presentation, thinking that Amazon probably spends a lot more on cars every year than the union does.

Union chairman Stuart Appelbaum said in an interview that the RWDSU buys cars for some representatives whose job it is to travel from workplace to workplace to organize campaigns.

Amazon said it wanted to explain to workers, especially those who have no prior knowledge of unions, that a union is a company that collects dues, and that it wants to explain how that dues can be used.

In another mandatory meeting, the two Bessemer workers told CNBC, Amazon circulated examples of previous contracts the RWDSU had won, trying to highlight the union’s shortcomings. Amazon also claimed that the RWDSU was primarily a poultry workers union with limited experience representing warehouse workers.

Appelbaum said poultry workers are a significant part of the RWDSU membership in Alabama, and many of the organizers who led the campaign and approached Amazon employees outside of BHM1 as they completed their shifts came from nearby poultry factories. The Union also represents workers in other industries, including retail, food manufacturing, nonprofit and cannabis, said RWDSU spokesperson Chelsea Connor.

In response to questions about whether it typified the RWDSU as a poultry union, Amazon said it wanted to emphasize to employees how well (or badly) the union could understand their employer.

During the meetings, Amazon also tried to highlight the negative results that could result from voting for the union. Amazon told workers the union could force workers to go on strike and workers could lose benefits in the future, workers told CNBC.

The Mid-South office of the RWDSU, which led the organization at Amazon, rebutted Amazon’s claim that the union would force BHM1 workers to strike, calling it a “tactic of fear,” according to workers’ reports. were distributed.

“Amazon has insinuated that the union will ‘pull you out of the strike,'” Randy Hadley, chairman of the Mid-South Council, said in a February letter to workers, which also addresses other claims from Amazon. “Here are the facts, our membership and our membership NOTHING BUT determines whether or not to strike with a super majority. This means that nearly 4,000 Amazon workers would have to vote to go on strike. A hit can be useful when needed, but it is also very, very rare. This is yet another Amazon fear tactic. “

Amazon said it wanted to point out to workers that if a union is voted on, the union could call for a strike because it is the union’s primary influence on an employer.

In response to whether it told employees that they could lose their benefits if they vote for a union, Amazon said it was striving to inform employees, as part of its general union training, that many results could come from collective bargaining.

Not the last attempt

Amazon workers, union leaders and employee advocates hope the Alabama loss won’t be the last attempt to organize the retail giant’s sprawling workforce.

There may also be future campaigns on BHM1. The worker who voted for the union said some pro-union workers have discussed the possibility of approaching the Teamsters and taking a future union action in their warehouse.

Elsewhere, Amazon employees and unions are considering different organizational strategies. The Teamsters communicate with Amazon drivers and warehouse workers at an Iowa facility and consider ways to muster workers outside of the election process. Amazon employees in Chicago have formed a group to organize employees at facilities in the area called Amazonians United Chicagoland

An employee at an Amazon facility in New Jersey, who also asked for anonymity, said they had previously approached a union about organizing their facility. After seeing the result in Bessemer, the employee said they went back to the drawing board and explored more informal tactics to achieve leverage.

Susan Schurman, a professor at the Rutgers School of Management and Labor Relations, pointed to the Alphabet Workers Union, a recently formed union of more than 800 Google employees, as a potential model for Amazon workers.

Unlike a traditional union, minority unions do not represent the majority of the workers. They are also not recognized by the NLRB and do not act as negotiating agents with employers.

However, Schurman said minority unions could serve as a “path to majority unions” and be a powerful tool for building worker support even before a formal campaign with the NLRB has started.

“Why not stay and build an organization and stick to it?” Schurman said. “Let workers recruit new members and demonstrate the value of a collective bargaining power.”

Appelbaum, the RWDSU president, said a strategy for a minority union is “worth considering.”

“We haven’t made a decision on that yet, but I think we’ll look at it,” said Appelbaum. “We know we’re not leaving.”