Scientists have made hollow cells out of cells that resemble human embryos in their earliest stages of development. The artificial embryos, called “blastoids,” could allow scientists to study early human development, infertility and pregnancy loss without experimenting with actual embryos.

Two separate research groups created these model embryos using different methods and each published their results March 17 in the journal Nature Portfolio.

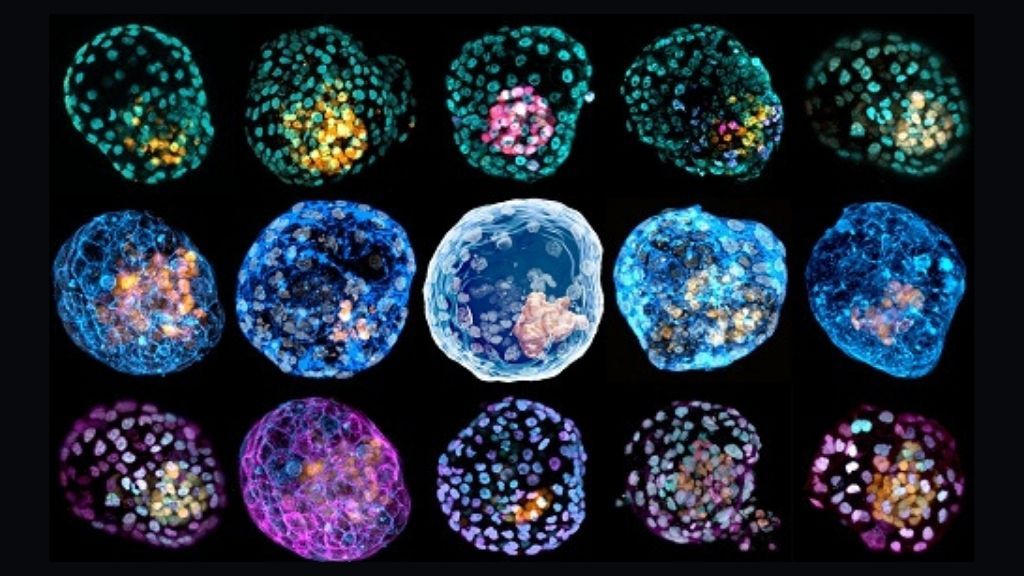

A research group started with adult humans skin cells, which they have genetically reprogrammed to resemble embryonic cells, according to a statementThe researchers then grew these modified cells on a 3D scaffold that guided them into a spherical shape. The resulting structure mimicked a human blastocyst, a structure that typically contains a few hundred cells and forms about four days after a sperm fertilizes an egg and later implants in the uterine wall, Nature News reported

The second research group started with humans stem cellsincluding both embryonic stem cells and stem cells derived from adult skin tissue, known as “induced pluripotent stem cells,” reported Nature News. The team treated the stem cells with specific chemicals known as growth factors to get them in the shape of a blastocyst.

Related: Inside life science: Once upon a stem cell

Both teams showed that their homemade blastocysts behaved similarly to real ones, in that they formed like hollow spheres and contained three different cell types that eventually form different parts of the body, like blastocysts, Nature reported. In addition, the bulbs could be “implanted” in a plastic sheet that served as a site for the human uterine wall.

Despite these similarities, neither model perfectly reconstructs a human embryo, and based on evidence from similar mouse models, the spheres are unlikely to develop beyond the blastocyst stage. Evidence suggests that mouse blastoids do not differentiate well into other cell types when implanted in a mouse uterus, possibly because of how their gene expression differs from true blastocysts, according to a 2019 report in the journal. Development cell

“I would consider this a significant advance in the field,” said Jianping Fu, professor of mechanical engineering at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, told NPR“This is really the first complete model of a human embryo.”

“With this technique, we can create hundreds of these structures. This allows us to increase our understanding of very early human development,” said José Polo, developmental biologist at Monash University in Australia and senior author of the first study. told NPR. “We think this will be very important.”

However, the experiments raise some serious ethical questions.

“I’m sure anyone who’s morally serious gets nervous when people start creating structures in a petri dish that are so close to early humans,” Daniel Sulmasy, a bioethicist at Georgetown University, told NPR. “The more they push the envelope, the more nervous I think someone would get people trying to create people in a test tube.”

As of now, the International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR) has a guideline that sets time limits on human embryo experiments in the laboratory, with a maximum of 14 days, Nature reported. This cap is designed to prevent the embryo from maturing beyond a point where its cells begin to differentiate into complex structures; during human pregnancy, the implanted blastocyst would form a “primitive streak” by day 14, indicating a shift towards this differentiation. Both research teams adhered to this rule in the new blastoid experiments.

The ISSCR plans to issue updated guidelines on embryo-like structures, such as these blastoids, in May 2021, Nature said.

In a report published in February 2020, the association stated that such models “would have great potential benefits for understanding early human development, for biomedical science, and for reducing the use of animals and human embryos in research.” Guidelines for ethical conduct of this work are currently not well defined, ” said Monash University statement.

Meanwhile, the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) will “continue to examine applications on a case-by-case basis,” said Carrie Wolinetz, NIH’s director of science policy, on March 11.

Originally published on Live Science.