Fecal transplants, which are already being studied as a treatment for intestinal infections and type 2 diabetes, may also help the body fight cancer, new US government-funded research suggests. In a small clinical trial, some advanced cancer patients who had the transplants started to respond to treatments that had not worked before, stabilizing or shrinking their tumors.

The purpose of a fecal transplant is to use a donor’s stool to reset a person’s gut microbiome, which is the neighborhood of bacteria that live along our digestive tract. The gut microbiome helps the body regulate everything from metabolism to a properly functioning immune system, and an unbalanced microbiome is believed to cause or increase the risk of many health problems, such as diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, and certain infections. By littering their digestive tracts with the bacteria from a donor’s stool, it seems possible to grow a healthier gut microbiome.

Currently, fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) is only considered an effective treatment for recurrent gastrointestinal infections caused by Clostridioides difficile, which can be fatal. But there are ongoing studies testing its use for other conditions. This new study, led by researchers at the National Cancer Institute, saw FMT as a kind of booster for another emerging treatment, cancer immunotherapy.

Immunotherapy uses drugs to enhance the immune system’s ability to find and kill cancer cells. These drugs include immune checkpoint inhibitors, which remove the natural limiter that some cancers use to avoid detection by T cells. While immune system inhibitors have shown promise in treating advanced cancers, some people’s tumors continue to resist immune suppression even after treatment. Some researchers have theorized that resetting the gut microbiome of these patients also makes these tumors vulnerable to immunotherapy.

G / O Media can receive a commission

“Cancer therapies often rely on stimulating anti-tumor immune responses, increasing the possibility that the gut microbiota could affect the host’s responses to cancer therapy through the immune system,” study author Giorgio Trinchieri, head of the Laboratory for Integrative Cancer Immunology in the United States. NCI center. for cancer research, Gizmodo told via email.

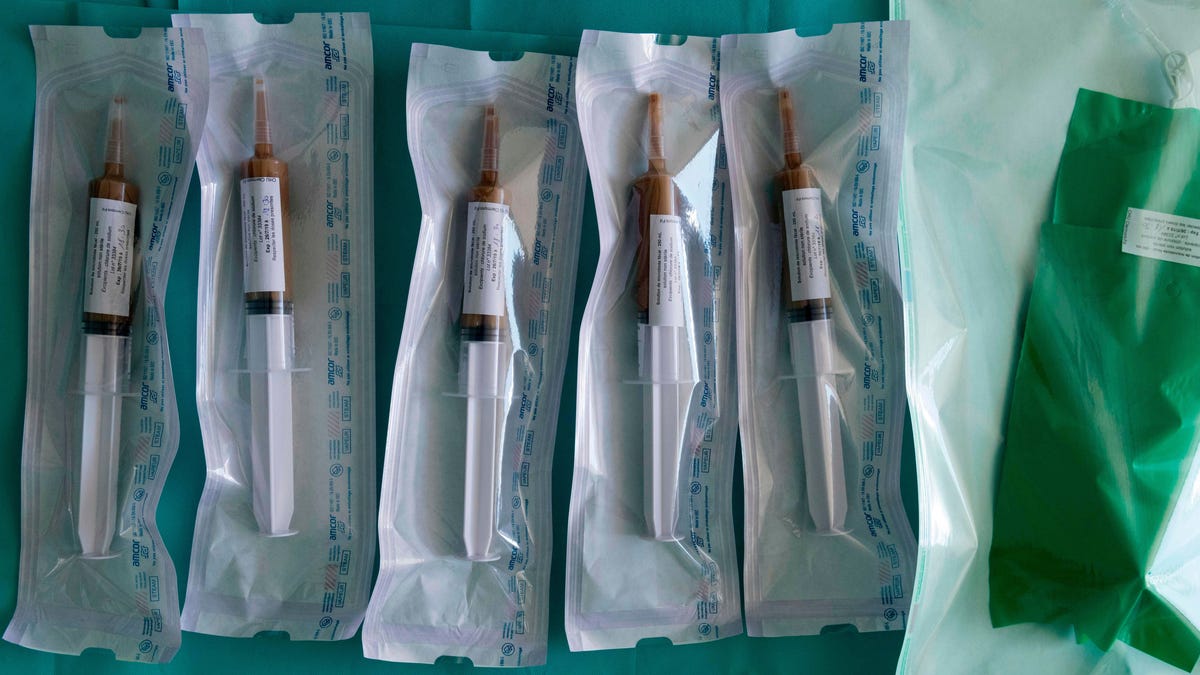

The study included 15 patients with advanced melanoma, the deadliest form of skin cancer, who had previously failed to respond to immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment. These patients received transplants from other patients with advanced melanoma who had responded to therapy (often patients receive a dose of antibiotics to clear up their existing ones microbiome, but not in this study). The donor stool was examined for potentially dangerous germs – a precaution that has become standard in the US waking of several diseases and one death related to fecal transplants with resistant bacteria in 2019.

Then six of the 15 patients started to respond to the treatment. In one patient, their tumors have continued to shrink and count for over two years, while in four others, their cancer has stabilized, with no signs of disease progression for at least a year. (The sixth patient appeared to be fully responsive to immunotherapy, but died of complications from unrelated surgery shortly after treatment.)

“In these patients the tumor progressed rapidly and life expectancy was short,” noted Trinchieri. “Stable disease and shrinkage of tumors would significantly improve the survival and quality of life of patients and could result in long-term survival and, in some cases, cure.”

Both the gut microbiome and immune system of these patients also showed signs of a beneficial change after transplantation, allowing for a better response to therapy. And the transplants themselves were well tolerated, although the immunotherapy likely caused minor side effects, including fatigue, in some patients. The findings appeared Thursday in the journal Science.

The study, according to Trinchieri, is one of the first to show that altering the gut microbiome can improve a person’s response to immunotherapy. And while this is only a proof-of-concept study, it also shows the potential of targeting the microbiome in general for cancer treatment.

Despite this potential, more work needs to be done with larger groups of patients before poop transplants can become a standard of care for difficult cases of cancer. The team and others’ research is beginning to identify the types of bacteria most likely to improve the response to immunotherapy, as well as the patients most likely to benefit from a transplant. They also keep a record of the patients who have responded to FMT, while using their donated poop for other studies.

In the future, this transplantation technique – which requires a colonoscopy – may not even be the preferred method of delivery. Instead, Trinchieri said, maybe we could get by just using a pill that contains the bacteria. Fortunately, some studies are already exploring that method, as well as the use of FMT for other types of cancer.