The effect of a drug, or the impact of a treatment such as chemotherapy, does not only depend on your body. The success of a particular drug also depends on the trillions of bacteria in your gut.

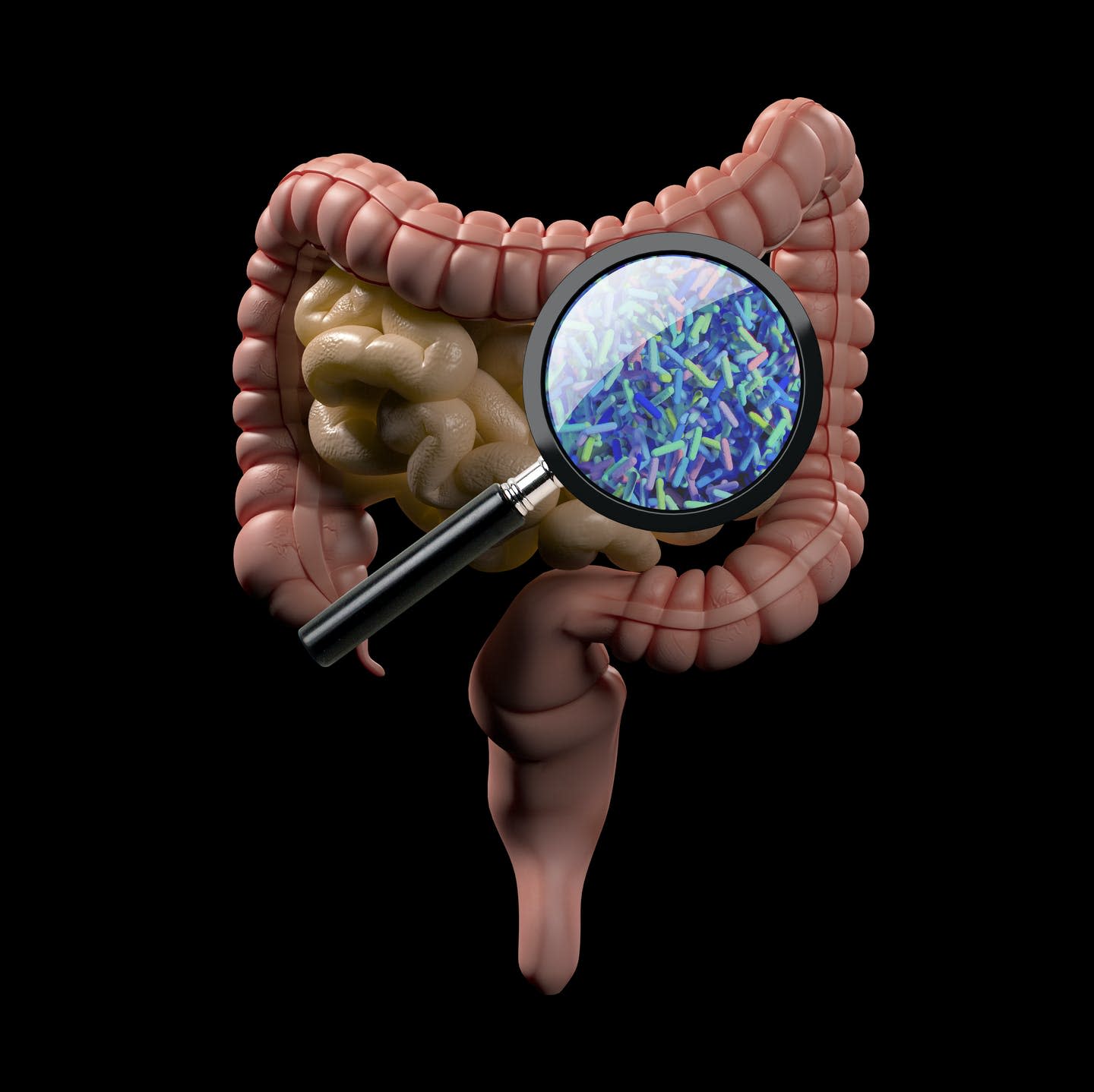

The 100 trillion bacteria that live in the human digestive tract – known as the human gut microbiome – help us extract nutrients from food, enhance immune response, and modulate the effects of drugs. Recent research, including mine, has implicated the gut microbiome in seemingly unrelated states, ranging from the response to cancer treatments to obesity and a host of neurological conditions, including Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, depression, schizophrenia and autism.

Underlying these seemingly discrete observations is the unifying idea that the gut microbiota sends signals outside the gut and that these signals have broad effects on a wide swath of target tissues.

I am a medical oncologist whose research is related to developing new therapies for melanoma. To evaluate whether altering the microbiome could benefit cancer patients, my colleagues and I evaluated the transfer of stool from melanoma patients who responded well to immunotherapy to those for whom immunotherapy failed. Our results, just published in the journal Science, show that this treatment helped shrink the tumors of advanced melanoma patients when other therapies had failed.

What connects cancer and gut bacteria?

Gut microbiota have been associated with the success and failure of multiple cancer treatments, including chemotherapy and cancer immunotherapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors such as nivolumab and pembrolizumab. In the more recent studies, the species and relative populations of gut bacteria determined the likelihood that a cancer patient would respond to drugs known as “immune checkpoint inhibitors.”

This study showed that differences in the gut microbiome between individual patients were associated with different outcomes of these drugs. But the precise mechanisms underlying microbiome-immune interactions remain unclear.

Can fecal microbes help to achieve hard-to-treat melanoma?

Oncologists often treat patients with advanced melanoma with the help of immunotherapies that target specific proteins on the surface of immune cells, known as PD-1 and CTLA-4. However, these work in a subgroup of patients: 50% -70% of patients have cancers that get worse despite treatment. No medical treatments have been approved for the treatment of melanoma patients who have failed PD-1 immunotherapy.

To investigate whether certain types of microbes can enhance the efficacy of PD-1 immunotherapies, my colleagues and I developed a study in which we collected fecal microbes from patients who had responded well to this therapy and administered them to cancer patients who did not benefit from it had. of the checkpoint medications.

We chose stool from patients who responded well to immunotherapy based on the suspicion that they might have higher amounts of bacteria involved in helping to shrink the cancer. Since it is difficult to identify one or two types of bacteria responsible for the beneficial response to these therapies, we used the entire bacterial community – hence fecal microbe transplantation.

Transplant recipients were patients whose melanoma had never responded to immunotherapy. Both recipients and donors underwent disease screening to ensure that no infectious agents would be transferred during the transplant. After a biopsy of their tumor, patients received a fecal microbe transplant from patients who benefited from immunotherapy, along with a drug called pembrolizumab, which was continued every three weeks.

My colleagues and I assessed the fecal microbe transplant 12 weeks after treatment. Patients whose cancers had shrunk or remained the same size after the fecal microbe transplant continued to receive pembrolizumab for up to two years.

Results of a new clinical trial

Following this fecal microbe transplant treatment, tumors from six of the 15 patients in the study had tumors that shrank or remained the same. The treatment was well tolerated, although some patients experienced mild side effects, including fatigue.

When we analyzed the gut microbiota of treated patients, we saw that the six patients whose cancer had stabilized or improved had a higher number of bacteria previously associated with responses to immunotherapy.

My colleagues and I also analyzed responders’ blood and tumors. By doing this, we saw that the responders had lower levels of unfavorable immune cells, called myeloid cells, and higher levels of memory immune cells. In addition, by analyzing proteins in the blood serum of treated patients, we observed decreases in the levels of key immune system molecules associated with resistance in responders.

These results suggest that introducing certain gut microorganisms into a patient’s colon may help the patient respond to drugs that enhance the immune system’s ability to recognize and kill tumor cells.

Ultimately, we hope to move beyond fecal microbe transplants to specific pools of microbes in cancers besides melanoma, paving the way for standardized microbe-based drug therapy to treat immunotherapy-resistant tumors.

[The Conversation’s science, health and technology editors pick their favorite stories. Weekly on Wednesdays.]

This article was republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit news site dedicated to sharing ideas from academic experts. It is written by: Diwakar Davar, University of Pittsburgh.

Read more:

Diwakar Davar receives research funding from Arcus Biosciences, BristolMyersSquibb (BMS), Checkmate Pharmaceuticals, CellSight Technologies, Merck, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK). Diwakar Davar receives a fee for advice from Checkmate Pharmaceuticals, Shionogi, Vedanta Biosciences.