But this appointment will be different. Since my last check up, Johnson & Johnson has been granted emergency use approval for its one-time vaccine against Covid. As a thank you to those of us who participated in the randomized, phase three vaccine trial, the company unblinds the participants and administers the vaccine to the placebo group.

I look forward to this unblinding with the same exuberance that I had as a child during Christmas week. All those presents under the tree waiting to be opened! But this time, my gift is protection against a deadly virus – an inoculation that literally saves lives.

My goal from day one was to help the nation overcome hesitation about vaccines and encourage people – especially people of color – to trust the vaccines. Since joining the trial, my efforts have been featured on People.com and in Essence magazine. I’ve had some friends tell me that my participation encouraged them to get vaccinated. On social media, some people have said they would consider giving it a shot now. I count these all as victories, but I know some minds are going to be harder to change.

Jamecka Britton, a 35-year-old black woman living in Atlanta, is one of these people who is reluctant to get the vaccine. Originally from Memphis, TN, she has a radiant smile that she says is consistently hidden behind an N95 mask everywhere she goes. She also has a warm sense of humor. I know because we have continued to inform each other about the pressure from the country to vaccinate as many people as possible – one makes a point, the other opposes. The messages are often littered with kind-hearted GIFs. What makes her position more remarkable to me is that she also happens to be a registered nurse.

Britton, who has been treating Covid-19 patients since the start of the pandemic, says the virus has affected every part of her community.

“It’s been extremely, extremely difficult,” Britton told me. “When it first started, I remember just coming home crying.”

She told me about the countless people she knows who have died from the coronavirus – except for the patients she has treated in the hospital. Their loss has also had its consequences.

“To see patients in their twenties with no pre-existing health problems,” she said, adding, “… they walked into the hospital, thought they had a cold, and the next day there was a ventilator and the doctor said there was there is really nothing else that they can do. “

But despite everything she’s been through thanks to Covid, she still hasn’t been vaccinated.

“I’m not against vaccines,” Britton clarified immediately. “I just feel like more tests need to be done on the vaccine to make sure it’s safe.”

As I have reported on vaccine hesitation, I have spoken to many people of color about their fears and have done some research to fully understand why this hesitation persists. During my morning walks, I listened to Isabel Wilkerson’s “Caste: The Origins of Our Disontents” and, as of 2007, Harriet A. Washington’s “Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present.”

From the decades-long Tuskegee experiment in which doctors stopped treatment for syphilis from unwitting black men to harvesting a piece of a cancerous tumor from Henrietta Lacks in the 1950s – tissue known as HeLa cells that remained the focus of years of study and medical breakthroughs – without her knowledge, there are undoubtedly some high-profile examples of medical professionals using black Americans for experiments without their consent.

However, as I speak to Britton and think back to what I gained from my research, I realize that it is likely that a less sensational and more personal history of individual physician-patient contract violations could really be the basis for suspicion of the science behind these new vaccines.

It is the myriad surgeries, amputations, and tests passed by blacks and other colored people on a case-by-case basis that may ultimately have disrupted a family member’s quality of life, allowing the doctors to study or perfect a technique before offering treatment . improved skill or medicine for their white patients. Oral stories of medical misconduct and disrespect have been shared in many black families, sparking generations of fear and distrust.

“I actually talk about it with my family on a daily basis. And to be honest, we are all very reluctant to get the vaccine given the history of malpractice and negligence in the African American community,” said Britton, who acknowledged this reality. . in its own roots. “I have, you know, family members who have expressed concern to me about testing and are, unquoted, lab rats like black people for vaccines.”

“I think it would probably be shocking to you to know that I was enrolling in a vaccination trial,” I told her, interested in how she would respond.

“No seriously?” she answered genuinely surprised. “I’m impressed. I’m really impressed.”

I told her that I was participating in the process of helping to neutralize the fear – a fear that I understand and must be acknowledged. “But I also know this is a different time. And the only thing that’s happened in America and that’s the good thing is we have a lot of health workers who look like you, who look like me, who look like our cousins, they are now at the forefront of designing and understanding the research and technology to make these vaccines, ”I explained.

What I’m trying to figure out, I tell Britton, is what could possibly be done to get people to take their photos.

“I’ve seen many of my colleagues who have received the vaccine and that is more incentive to get vaccinated. However, I would still like to see a large number of African Americans get the vaccine,” explained Britton. “A lot of colored doctors I know are unwilling to get the vaccine, so that still makes me hesitant.”

“So if you saw doctors all over the country and we have a lot of black doctors, would that help?” I asked.

“That would help,” she replied.

This is an angle tackled by the Black Coalition Against Covid and the Kaiser Family Foundation, which highlights black scientists, doctors and nurses endorsing the vaccines in a question-answer montage of on-camera interviews and testimonials with comedian and host of CNN’s “United Shades of America” W. Kamau Bell.

“When the vaccine came in, I felt a tremendous honor,” said Dr. Valerie Montgomery Rice, president of Morehouse School of Medicine, in the video.

Of course I sent the video to Sister Britton – followed by a photo of one of my doctors, who happens to be a black woman, who is getting her vaccination.

The whole point is to add more voices to the mix of people of color proudly letting the world know they got their chance and encouraging others to do the same. The goal is to get more people vaccinated so that we can live long, healthy lives and move beyond this pandemic.

“This is the big moment!”

As for me, while I wait to find out if I got the real vaccine or placebo in December, I go back and forth in my head about which category I think I fall into. The animals in the framed prints on the wall – and ode to Ark Clinical’s name – stare at me. I hope the rise of vaccinations helps us all.

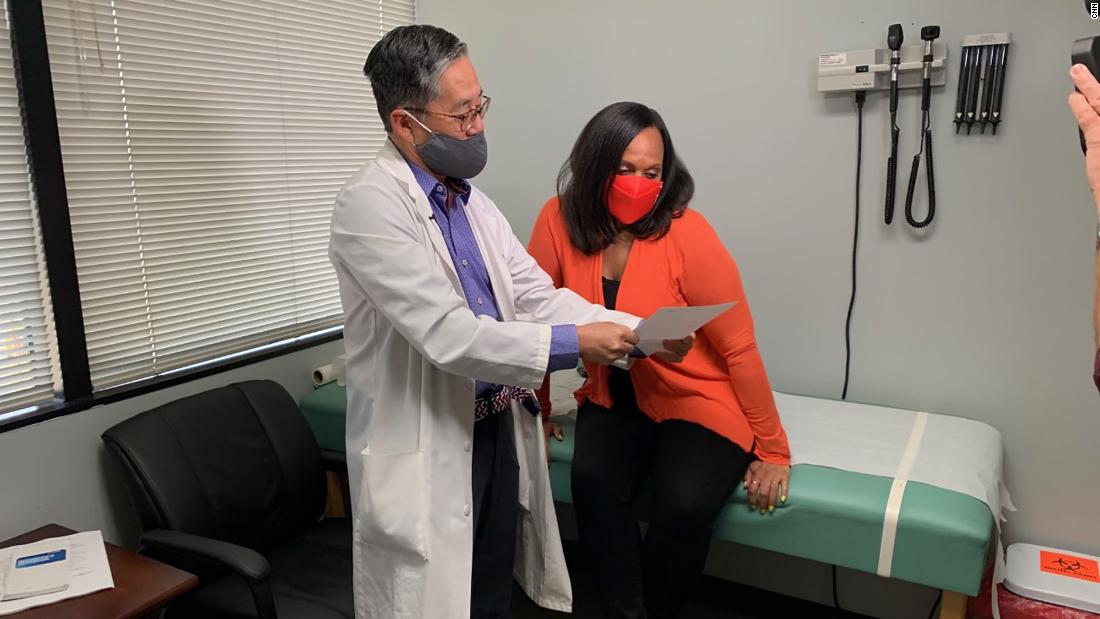

“This is the big moment!” said Dr. Kenneth Kim, medical director and CEO of Ark Clinical Research, when he entered the room. Neither of us know my vaccination status. Nurse Amber Mottola gives him a sheet of paper. “Okay, so we’ll look at this together,” said Dr. Kim to me. “So what does it say?”

“I’ve got the placebo!” I read aloud, Dr. Kim repeated the same words. I thought I got the real thing.

Although it turned out that I had not been vaccinated before, I was about to be vaccinated. Mottola already had a needle ready.

My experience with Covid vaccine research has all been positive. I need to see up close how these trials work; I feel better informed to have conversations about vaccine hesitation and now I am given the gift of vaccination. “Anyway, today is a good day,” I tell them.

“Thank you for being a pioneer because if there weren’t people like you who volunteered, we would never have approved this vaccine,” said Dr. Kim in response before giving me the game plan. “We are going to note the time when we administer your dose and then there will be a 15 minute observation.”

“Okay! I’m still very excited,” I exclaimed, the smile on my face clearly visible even with my mask on.

“You waited a long time for this, and you deserved it!” Mottola said as she cleaned a spot on my arm and slid the needle into it. “One, two – Full dose!”

“Oh yeah! That definitely felt different,” I said, noting that the vaccine felt heavier in my arm than the placebo.

“Vaccinated!” both Amber and Dr. Kim cheers.

With just one chance, I now get the protection I wish for all Americans. For the next two weeks, my body will fully build its response to the deadly coronavirus.

I still can’t stop smiling under my mask.