AUSTIN, Texas – Producing clean water at a lower cost could be on the horizon after researchers at the University of Texas at Austin and Penn State solved a complex problem that had baffled scientists for decades until now.

Desalination membranes remove salt and other chemicals from water, a process critical to the health of society, purifying billions of gallons of water for agriculture, energy production and drinking. The idea seems simple – push salt water through and clean water comes out on the other side – but it contains complex intricacies that scientists are still trying to understand.

The research team, in collaboration with DuPont Water Solutions, has solved an important aspect of this mystery and opened the door to lowering the cost of producing clean water. The researchers found that desalination membranes are inconsistent in density and mass distribution, which can hinder their performance. Uniform nanoscale density is key to increasing the amount of clean water these membranes can create.

“Reverse osmosis membranes are widely used for cleaning water, but there is still a lot we don’t know about them,” said Manish Kumar, associate professor in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at UT Austin, who co-led it. research. “We couldn’t really tell how water moves through it, so all the improvements over the past 40 years have been essentially done in the dark.”

The findings are published today in Science.

The document documents an increase in efficiency of the tested membranes by 30% -40%, meaning they can clean more water with significantly less energy. That could lead to better access to clean water and lower water bills for both individual homes and large users.

Reverse osmosis membranes work by applying pressure to the salt feed solution on one side. The minerals stay there while the water flows through them. While it is more efficient than non-membrane desalination processes, it still consumes a large amount of energy, the researchers said, and improving the efficiency of the membranes could reduce that load.

“Freshwater management is becoming a critical challenge around the world,” said Enrique Gomez, a professor of chemical engineering at Penn State who co-led the study. “Shortages, droughts – with increasing severe weather patterns, this problem is expected to worsen. Having clean water is critical, especially in resource-poor areas. “

The National Science Foundation and DuPont, which makes numerous desalination products, funded the research. The seeds were planted when DuPont researchers found that thicker membranes actually turned out to be more permeable. This came as a surprise because conventional science has been that thickness decreases how much water can flow through the membranes.

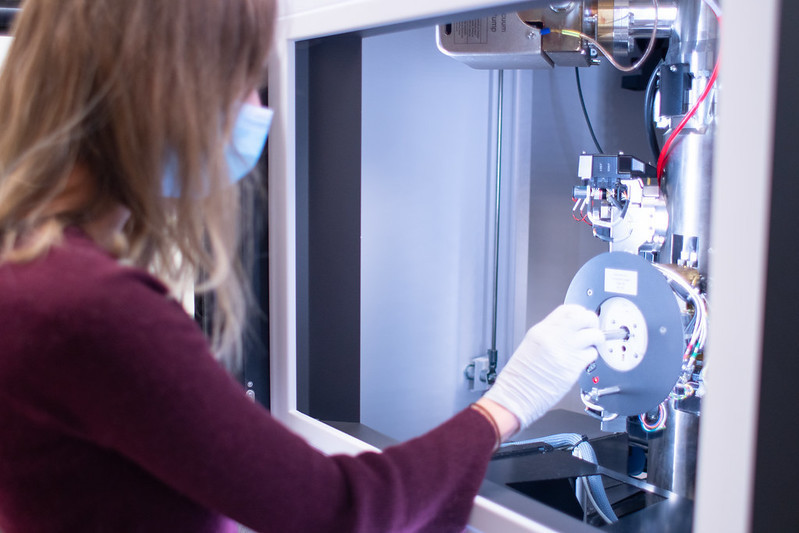

The team connected with Dow Water Solutions, which is now part of DuPont, in 2015 during a ‘water summit’ organized by Kumar, and they were eager to solve this mystery. The research team, which also includes researchers at Iowa State University, developed 3D reconstructions of the nanoscale membrane structure using state-of-the-art electron microscopes in Penn State’s Materials Characterization Lab. They modeled the path that water takes through these membranes to predict how efficiently water can be cleaned based on the structure. Greg Foss of the Texas Advanced Computing Center helped visualize these simulations, and most of the calculations were performed on Stampede2, TACC’s supercomputer.