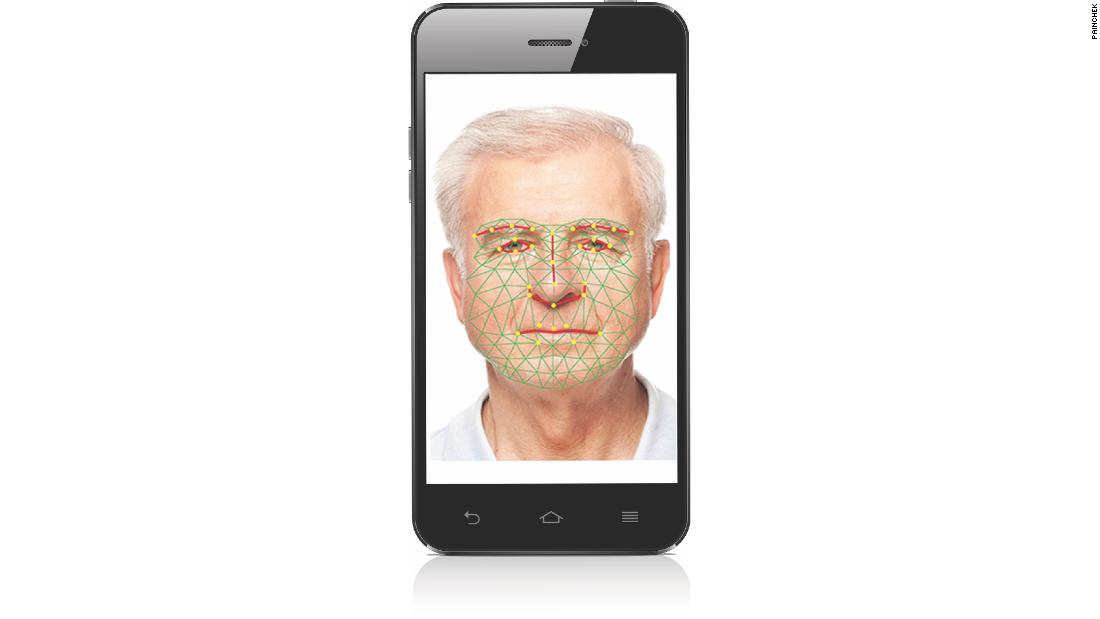

A caregiver records a short video of the patient’s face using a smartphone and answers questions about their behavior, movements and speech. The app’s AI recognizes facial muscle movements associated with pain and combines it with the caregiver observations to calculate an overall pain score.

According to the company, PainChek can detect pain with more than 90% accuracy and more than 180,000 pain assessments have been conducted on more than 66,000 people worldwide. The app is designed for use with elderly people in need of care.

A team of Scientists from the School of Pharmacy at Curtin University in Western Australia began developing PainChek in 2012. They wanted to find a better alternative to subjective paper-based ratings.

“It’s very difficult for people to decipher the emotions of someone’s face,” explains Peter Shergill, PainChek’s director of business development. “So the tool applies artificial intelligence and algorithms to decode the face based on decades of research.”

“Globally, the assessment of pain in people with dementia is not strong,” Shergill says. “Where pain goes unnoticed or untreated in people with dementia, it can manifest itself in behavior that is difficult to control, which people then try to control with antipsychotic medications, which carries further risks.”

In 2019, the Australian government allocated up to 5 million Australian dollars ($ 3.8 million) to nursing homes in the country to adopt PainChek as part of a two-year trial. “It aims to improve the diagnosis and management of pain, quality of life and health outcomes for people living in residential care,” said Richard Colbeck, the federal minister for Senior Australians and Aged Care Services.

Interpreting feelings

PainChek says its technology is currently used in more than 722 care homes worldwide. It was launched in the UK last August, where it has been used by around 1,000 patients to date.

Paul Rowley owns a 24-bed home in the UK and has been using PainChek for almost a year. He says 20 of his residents are diagnosed with dementia.

“[People with dementia] have difficulty communicating and cannot necessarily articulate what they feel, which means that the caregiver often has to interpret their feelings, ”says Rowley. He says the app helps caregivers quickly determine if someone is in pain.

PainChek is also an important tool for Rowley to demonstrate the absence of pain. He gives an example where he and his employees could use the app to prevent a woman from receiving unnecessary medication.

“We have a lady who is very advanced in her dementia and she showed signs that most people would interpret as physical pain,” he says. “But we knew the lady very well and were convinced that what she was manifesting was in fact not pain, but frustration and fear, and we used PainChek to demonstrate that.”

PainChek is also looking for products for other groups. It has conducted research at a children’s hospital in Melbourne to help develop an app to identify pain in children under the age of three.

“We’re looking at learning disabilities, delirium and end of life, as well as further additions,” Shergill says. “We have a unique solution that is transferable across ethnicities and backgrounds … users can see the impact they are having.”