A supermassive black hole is racing through the universe at 110,000 mph and the astronomers who saw it don’t know why.

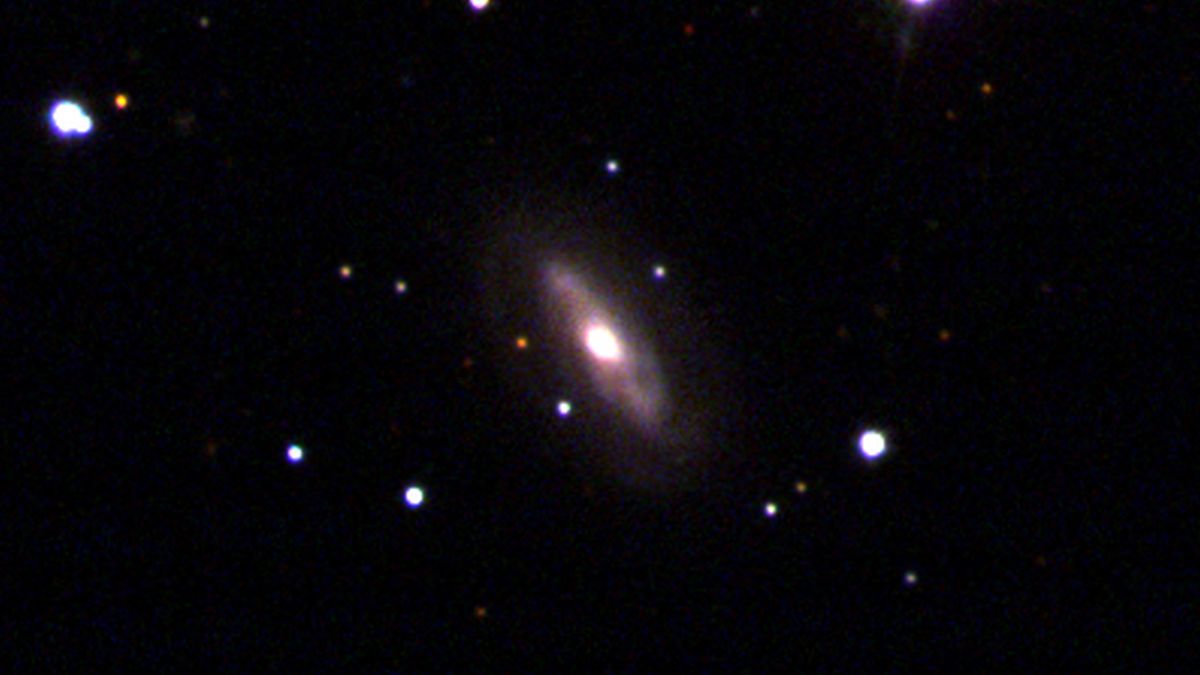

The fast-moving black hole, about 3 million times more massive than our Sun, races through the center of the galaxy J0437 + 2456, about 230 million light-years away.

Scientists have long theorized that black holes can move, but such a movement is rare because their gigantic mass requires an equally tremendous force to get them going.

Related: The 12 strangest objects in the universe

“We don’t expect the majority of supermassive black holes to move; they are usually content to just stay put,” Dominic Pesce, study leader and astronomer at the Harvard and Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, said in a statement

To begin their search for this rare cosmic event, the researchers compared the speeds of 10 supermassive black holes with the galaxies they centered, focusing on the black holes with water in their accretion disks – the spiral collections of cosmic material in orbit around the black holes.

Why water? As water orbits in a black hole, it collides with other material, and the electrons surrounding the hydrogen and oxygen atoms that make up water molecules are excited to higher energy levels. When these electrons return to their ground state, they emit a beam of laser-like microwave radiation called a maser.

Using a cosmic phenomenon known as redshift, where the light from moving objects is stretched to longer (and thus redder) wavelengths, the astronomers were able to observe the degree to which the maser light was shifted from the accretion disk. away from its known frequency when stationary, thereby measuring the speed of the moving black hole.

They took more observations from different telescopes and combined them all using a technique called Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI); This technique allowed the researchers to combine the images from different telescopes to effectively behave like an image captured by a very large telescope, about the size of the distance between them. That way, the scientists could precisely measure the speed of the black holes from which it originated.

One of the telescopes the researchers used for the experiment was the Arecibo Observatory, which has since been decommissioned after the instrument platform crashed on the telescope’s disk in December 2020.

Of the 10 black holes they measured, nine were at rest and one was in motion. While 110,000 mph (177,000 kph) is pretty fast, it’s not the fastest supermassive black hole. Scientists previously clocked a supermassive black hole hurtling through space at 5 million mph (7.2 million kph), they reported in 2017 in the magazine. Astronomy and Astrophysics

The researchers don’t know what made such a heavy object move at such a high speed, but they came up with two possibilities.

“We may be observing the aftermath of two supermassive black holes merging,” Jim Condon, a radio astronomer at the National Radio Astronomy Observatory, said in a statement“The result of such a fusion can cause the newborn black hole to recoil, and we can watch it recoil or settle down.”

The other possibility is considered much rarer and newer by astronomers: the supermassive black hole could be part of a pair with another black hole that is invisible to their measurements.

“Despite all the expectations that they really should be plentiful, scientists have had a hard time identifying clear examples of binary supermassive black holes,” Pesce said. “What we might see in the galaxy J0437 + 2456 is one of the black holes in such a pair, while the other remains hidden from our radio observations due to the lack of maser emission.”

If the black hole is dragged through an even larger, invisible hole, this could explain why it is traveling so fast, but more observations are needed to get to the bottom of the mystery.

The group published its findings online March 12 in The Astrophysical Journal.

Originally published on Live Science.