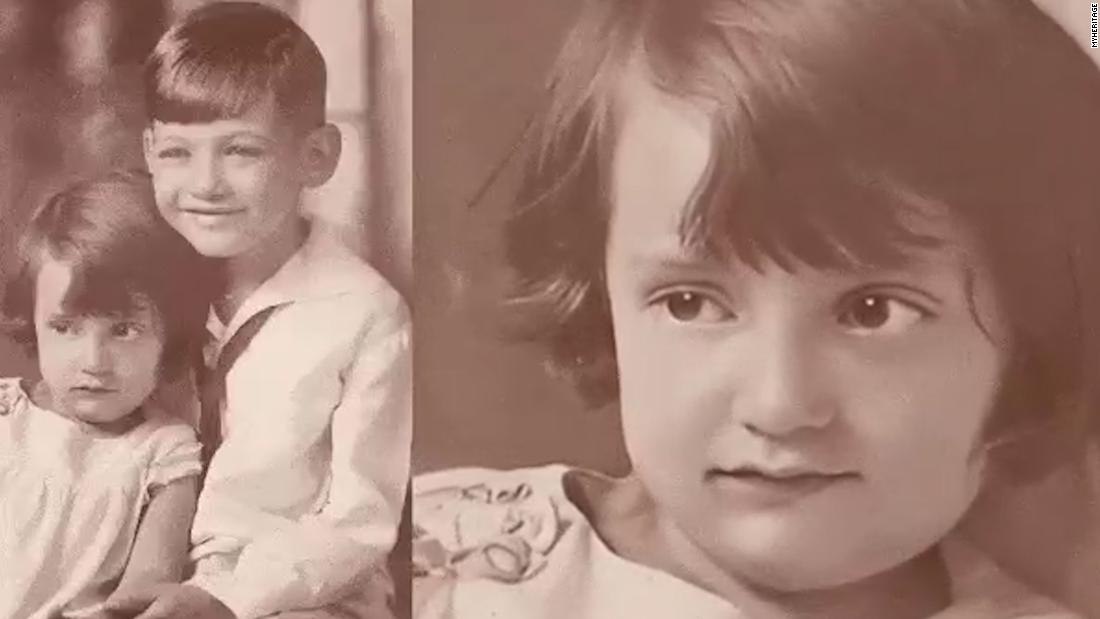

As far as AI animated images go, the technology behind these Harry Potter-esque photos isn’t particularly complex.

Users are invited to provide old photos of their loved ones, and the program uses deep learning to apply predetermined movements to their facial features. It also compensates for minor moments not in the original photo, such as revealing teeth or the side of a head. Together it creates a, if not a completely natural effect, then a very captivating effect.

We rely on perception and emotion

Fascinating – and yes, a bit scary.

“Indeed, the results can be controversial and it is difficult to remain indifferent to this technology,” their FAQ page reads.

When it is a beloved family member who actually occupies that almost-but-not-all of space, the parts of our brain that love and fear face each other, even when we know very well that what we are looking at is not real.

“The way our brain processes images of humans is different from inanimate objects. It uses neural circuits,” says Farid. “For years we have been able to synthesize inanimate objects, and that completely fools the visual system because we have no preconceived ideas about how they move. But when it comes to people, it lags behind. subtle way, we move and recognize these movements. “

AI relies on data and rules

These kinds of applications look for a similar kind of human connection as Deep Nostalgia. But the fact is that artificial intelligence has nothing human.

Farid points out that machine learning, which is the engine of more widely available animation technologies such as Deep Nostalgia, is a field within the wider world of artificial intelligence. Machine learning delves into data and finds patterns. While a program may get better with more input, no intelligence or analysis is involved in how it applies these patterns.

There are many applications that benefit greatly from this type of data.

“When you forecast the stock market, you want patterns,” Farid gives as an example. Or making cancer diagnoses. I don’t need to understand at this point why cancer shows up, I just want to know if it is. ‘

When applied to more human pursuits, the lack of, well, intelligence shows.

The smiling faces of our ancestors, while moving, of course, do not hold up when we drop our suspension of disbelief.

However, those inconsistencies will diminish as the technology develops, and Farid says it’s time for companies to take a critical look at the ethical implications of using it.

“The tech industry has done things because they can and not because they should,” he says. “We need to stop building things because they’re cool and start asking these tough questions before it’s too late.”

For example, technology used to be so good that our emotions can transcend our keen senses.

In the future, maybe another program will be able to fill those gaps, and we will be able to see, hear, and talk to those who have been lost long before us. Such technology will pose astonishing challenges to our security and our sense of reality as we know it.

But when it smiles at us through the comforting faces of our closest loved ones, it will be much more difficult to resist.