An enormous black hole continues to slip through the nets of astronomers.

Supermassive black holes are thought to lurk in the hearts of most, if not all, of the galaxies. For example, our own Milky Way has one as massive as 4 million suns and M87’s – de only black hole ever directly depicted – tilts the scales at no less than 2.4 billion solar masses.

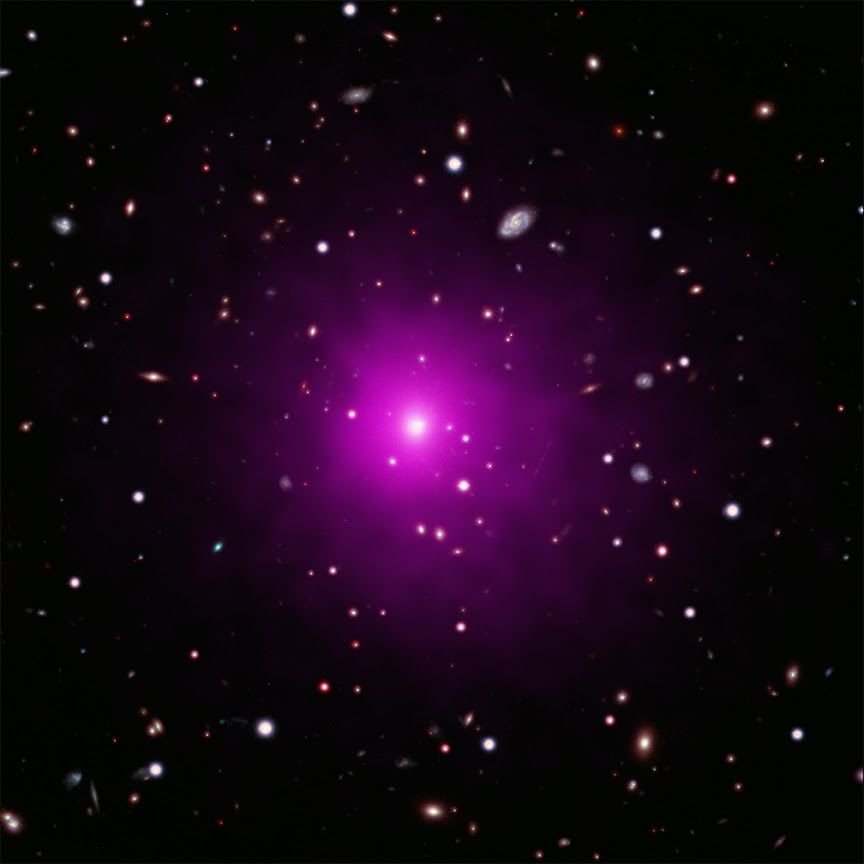

The large galaxy at the core of the Abell 2261 cluster, which is about 2.7 billion light-years from Earth, should have an even larger central black hole – a light-abrasive monster weighing as much as 3 billion to 100 billion suns, astronomers estimate based on the mass of the galaxy. But the exotic object has so far escaped detection.

Related: Historical first images of a black hole show Einstein was (again) right

For example, researchers previously looked at X-rays streaming from the center of the galaxy, using data collected by NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory in 1999 and 2004. X-rays are a potential signature of a black hole: When material falls into the mouth of a black hole, it accelerates and warms up enormously, emitting a lot of high-energy X-ray light. But that hunt yielded nothing.

Now, a new study has conducted an even deeper search for X-rays in the same galaxy using Chandra observations from 2018. And this new effort didn’t just look at the center of the galaxy; it also took into account the possibility that the black hole was struck towards the hinterland after a monster galactic fusion.

When black holes and other massive objects collide, they cast ripples in space-time known as gravitational waves. If the emitted waves aren’t symmetrical in all directions, they could push the merged supermassive black hole away from the center of the newly enlarged galaxy, scientists say.

Such “recoiling” black holes are purely hypothetical beings; no one has definitively seen one yet. Indeed, “it is not known if supermassive black holes even get close enough to each other to produce and merge gravitational waves; so far, astronomers have only verified the mergers of much smaller black holes,” NASA officials wrote in a report. statement about the new study.

“The detection of receding supermassive black holes would encourage scientists to use and develop observatories to look for gravitational waves coalescing from supermassive black holes,” she added.

Abell’s central galaxy 2261 is a good place to hunt such a unicorn, researchers said, as it shows several possible signs of a dramatic merger. Observations by the Hubble Space Telescope and the ground-based Subaru telescope show that its core is the area of highest star density much bigger than expected for a galaxy of its size. And the densest stellar patch is about 2,000 light-years from the center of the galaxy – “remarkably distant,” NASA officials wrote.

In the new study, a team led by Kayhan Gultekin of the University of Michigan found that the densest concentrations of hot gas were not in the central regions of the galaxy. But the Chandra data did not reveal significant X-ray sources, either in the galactic core or in large clumps of stars further away. So the mystery of the missing supermassive black hole remains.

That mystery could be solved by Hubble’s successor – NASA’s big, powerful one James Webb space telescope, which is expected to launch in October 2021.

If James Webb does not see a black hole in the heart of the galaxy or in one of its larger stellar clumps, “the best explanation is that the black hole has retreated far from the center of the galaxy,” NASA officials wrote.

The new study has been accepted for publication in a journal of the American Astronomical Society. You can read it for free on the online preprint site arXiv.org.

Mike Wall is the author of “Outside(Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), a book about the quest for alien life. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.