Man-made climate change “may have played a key role” in the coronavirus pandemic. That’s the conclusion of a new study examining how climate changes have transformed Southeast Asia’s forests, resulting in an explosion of bat species in the region.

The researchers found that, due to changes in vegetation over the past 100 years, an additional 40 bat species have moved to the region, along with 100 other bat-borne coronaviruses. Bats are known carriers of coronaviruses, with different species carrying thousands of different species. Many scientists believe the virus is the cause of the global COVID-19 pandemic originated in bats in southern China’s Yunnan province or adjacent areas before it crossed the people.

These findings have concerned scientists about the likelihood that climate change will make future pandemics more likely.

“If bats with about 100 coronaviruses spread to a new area as a result of climate change, it seems likely that this will increase, rather than decrease, the likelihood that a coronavirus harmful to humans will be present, transferred or evolved in this area,” explains Dr. Robert Beyer, lead author of the study and researcher at the University of Cambridge.

From Han Guan / AP

The researchers used climate records to create a map of the world’s vegetation as it was a century ago. Using knowledge of the type of vegetation required by different bat species, they determined the global distribution of each species in the early 20th century.

They then compared this to current bat populations. Their results show that the wealth of bat species – the number of different bat species found in a given area – is flourishing more in this part of Southeast Asia than in any other place on Earth.

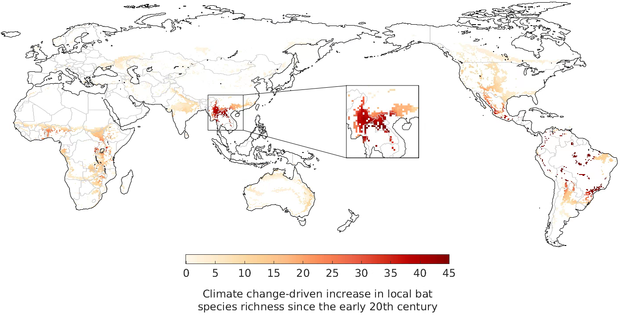

The image below, taken from the study, shows how the forests of southern China, Myanmar and Laos have changed over the past century, improving the habitat of bats and allowing more species to spread. This clear rose over the region shows the increase in the wealth of bat species. (The study does not take into account the total population size, only the diversity of bat species in the area.)

Dr. Robert Beyer

According to the authors, climate changes such as temperature rises, sunlight and carbon dioxide, which affect the growth of plants and trees, have altered the composition of the vegetation in southern China, turning tropical scrub into tropical savannah and deciduous forests. According to the authors, this type of forest is more suitable for bat species.

The study calls this area of Southeast Asia “a global hotspot” for bat species and points to genetic data suggesting that SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, originated in this region.

This, the authors say, is the first evidence of how climate change may have played a direct role in the origin of the virus.

“We estimate that over the past century, climate change has caused a significant increase in the number of bat species at the site where SARS-CoV-2 is likely to originate,” Beyer said. “This increase suggests a possible mechanism for how climate change could have played a role in the origins of the pandemic.”

A team of researchers from the World Health Organization was finally admitted in Wuhan, China, in January to investigate the source of the outbreak, which was first reported in that city a little over a year ago. A leading theory among scientists is that the virus originated in bats before it jumped to humans, possibly through an animal host pangolins. Some of the first cases were related to a game market in Wuhan. But as of now, this is just a theory, and so are researchers just started to formally investigate the origin of the pandemic.

Dr. Rick Ostfeld, an expert on disease ecology at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies in Millbrook, New York, finds the research compelling, even though he disagrees with all of the conclusions. He says it is not surprising that climate change has changed forests and bat communities. He also agrees with the study’s authors that animal movement can help spread viruses.

“Moving animal communities in a region can have a major impact on disease transmission by exposing animal hosts to new pathogens,” he said.

But otherwise he is cautious about drawing conclusions.

“The connection with the emergence of coronaviruses is highly speculative and seems unlikely,” said Ostfeld.

“What the study is apparently doing wrong is the assumption that the increased diversity of bats (which they presume) leads to an increased risk of a bat-borne virus hitting humans. This is simply not the case,” he said. “The vast majority of bats are harmless to humans – they don’t harbor viruses that can make us sick. So adding more of those species doesn’t increase the risk.”

Kate Jones, professor of ecology and biodiversity at University College London, is also somewhat reluctant. She said, “Climate change certainly plays a role in changing species distribution to increase ecological hazard. However, the risk of spillover effect is a complex interplay of not only ecological hazards but also human exposure and vulnerability.”

Beyer agrees that “caution is warranted” when it comes to directly linking climate change with the pandemic because, as he explains, assessing the extent to which climate change contributed to each stage between a bat carrying the virus carries and a human who becomes infected. will take a lot more work. In particular, this involves the use of epidemiological models that analyze the interactions of different species and viruses in space and time.

Although it is widely believed that exponential growth of the human population and our unbridled exploitation of the natural world, such as destroy forests and expanding the pet trade, is increasing the risk of infectious pathogens making the jump from animal to human easier is the degree to which that is less clear climate change factors.

AP

However, human-induced climate change has warmed many ecosystems over the past century – sometimes by several degrees – and rainfall patterns have shifted, with some areas becoming less and others more. These ecosystem changes shift the habitats of many species, bringing more species into contact with each other, potentially allowing viruses to spread more easily.

When asked about the climate links with the spread of disease, most experts agree there is an impact, but some say direct human actions such as deforestation, development or industrial animal husbandry are of greater concern.

“It may turn out that increases in human populations, human movement and degrading natural environments from agricultural expansion play a more important role in understanding the SARS-CoV-2 spillover process,” explains Jones.

Ostfeld noted, “We can predict which animal species are most likely to carry pathogens that can make humans sick. These are generally the ones that thrive if we replace natural habitats (such as forests and savannas) with agriculture, residential areas and shopping centers. “

Beyer has no objection to those assessments. “We strongly agree that the expansion of urban areas, farmland and hunting grounds into natural habitats is a major cause of the transmission of zoonotic diseases – they are what connects many pathogen-carrying animals and humans in the first place”, he said.

But given the findings of his research into how climate has reshaped the region, Beyer thinks climate change could be a major driver.

“Climate change can drift where these animals occur; in other words, climate change can bring pathogens closer to humans. It can also bring a virus-carrying species to another species’ habitat where the virus can then jump -” a step that might not have happened without climate change, and that could have major long-term implications for where the virus can go. ”

Beyer also sees climate links that go beyond just the increase in bat species. “In some cases, higher temperatures can increase viral load in species, making the virus more likely to be transmitted,” he said. “And, an elevated temperature can increase the tolerance of viruses to heat, which in turn can increase infection rates, as one of our main defense systems against infectious diseases is to raise our body temperature (fever).”

While there is some caution in the scientific community about the specific impact of climate change on the current coronavirus pandemic, there is widespread agreement that climate change will become an ever greater driver of emerging infectious diseases and pandemics in the future.

“Climate change will shift the geographic distribution of pathogen-bearing species to overlap with species with which they previously did not overlap,” Beyer said. “These new interactions will provide dangerous opportunities for viruses to spread and evolve.”

“Climate change is definitely a major driver for the onset and spread of disease. It can increase transmission in a number of ways,” said Ostfeld. “So yes, climate change certainly concerns me as a driver of future pandemics.”