How exactly happened perhaps hundreds of millions of years ago, however, it has long been an evolutionary mystery that puzzled scientists.

Now US scientists say they may have stumbled upon a possible answer.

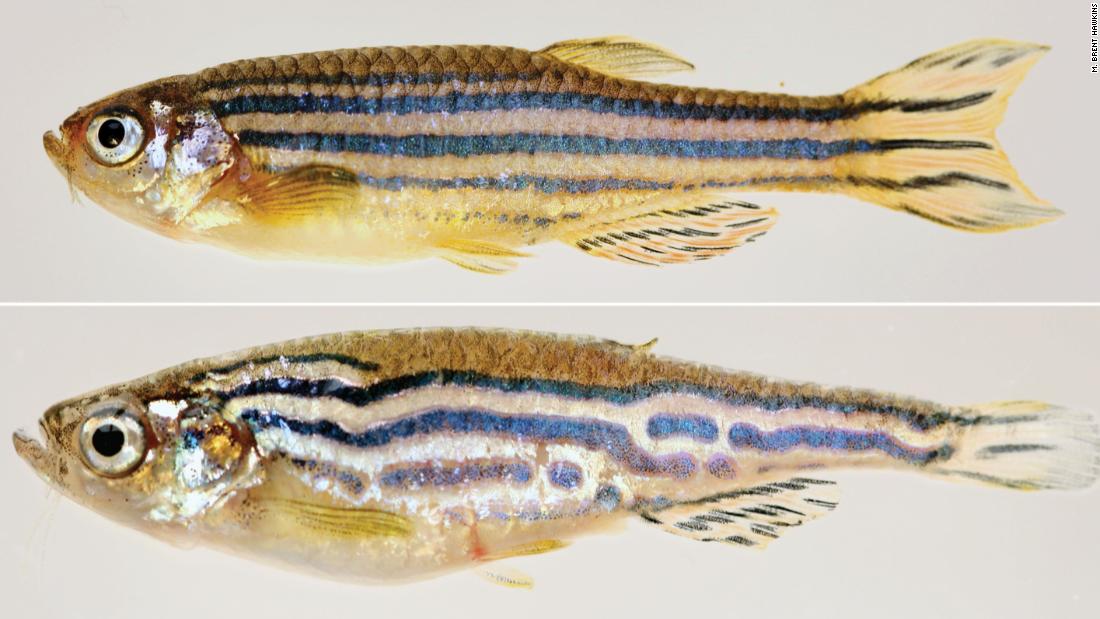

By modifying a single gene, researchers at Harvard University and Boston Children’s Hospital developed zebrafish that displayed the onset of limblike appendages.

To answer how animals made the transition from sea to land, scientists have traditionally looked at the fossil record. But over the past 30 years, scientists have been looking for changes in genes that could explain the shift from fin to modern limbs.

“Before this discovery, the transition from fin to limb was believed to involve frequent changes in many genes,” he noted via email.

“Of course this transformation was still a very gradual and complex process, but our mutants show that there may also be fast jumps involved, and that developing animals can absorb new bones quite easily.”

Innate quality

While previous research has identified genes needed to make fin and limb bones, no one has previously found a genetic change that causes a fin to shift into a more limblike pattern, Hawkins explained via email.

The mutation the researchers found causes a change in the zebrafish’s pectoral fin bones, which attach a bit to the fish’s shoulder joint, much like the human arm attaches to the shoulder.

A new series of long bones – called intermediate radians – develop, creating a joint that resembles a human elbow. The genetic change includes new muscles and joints found in limbs, but not the simple fins.

The scientists’ discovery has shown that the fish, thought to have lost the machinery needed to develop empty body parts, in fact retain an innate ability to form these structures.

Miniature-sized zebrafish have become a mainstay of genetic research. They are easy to keep in large numbers and breed easily, with a single pair producing hundreds of eggs every week. These fish are also gentle and easy to handle, and their eggs and embryos are translucent and easy to examine.

The researchers randomly mutated the zebrafish genes and then systematically examined the fish to find those that underwent interesting changes in their shape – in this case, the limblike structures.

This genetic link between fins and limbs could, with more research, shed light on how some animals made the transition from sea to land and what genetic mechanics are required to do so.

One question the team then hopes to explore is whether the new bones change how the zebrafish’s fins work and how the fish moves.

“That such complex and coordinated changes could result from altering a single letter of DNA was quite shocking, revealing that our fish-like ancestors had the raw genetic material and latent capacity to create limbs,” Hawkins said.