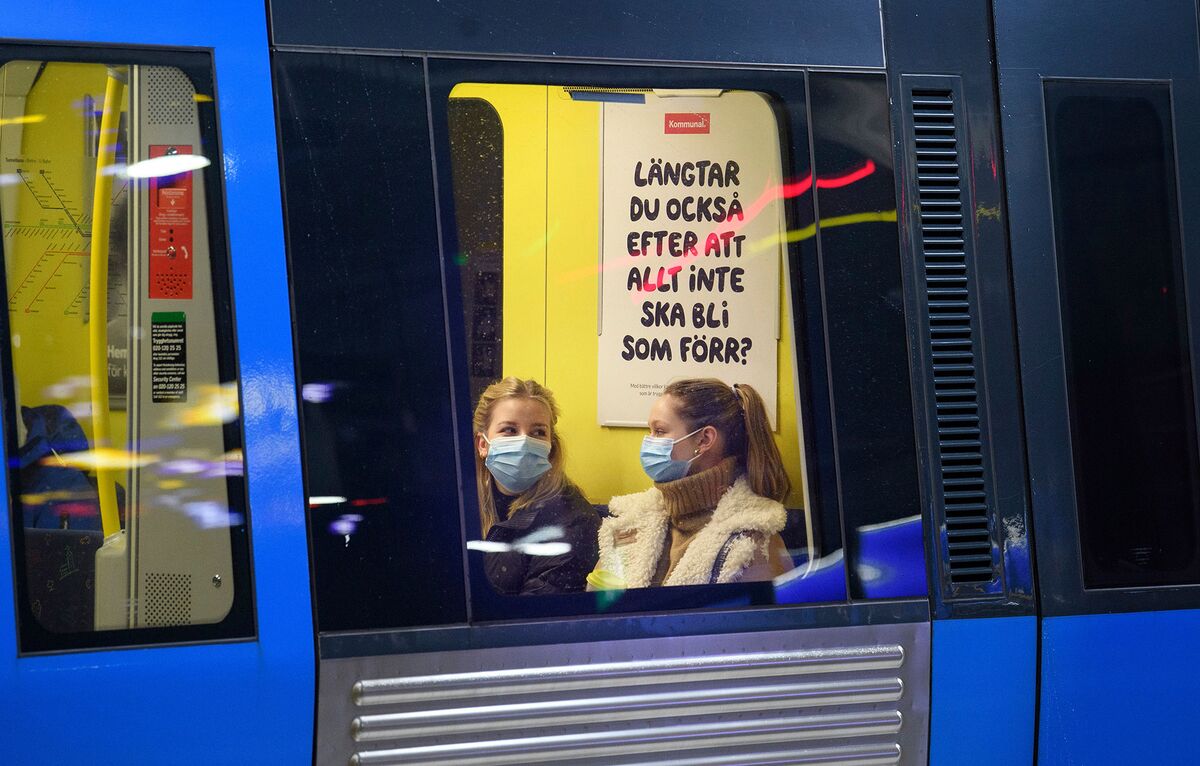

Passengers in a metro in Stockholm.

Photographer: Jessica Go / AFP / Getty Images

Photographer: Jessica Go / AFP / Getty Images

Sweden’s hands-off response to Covid-19, avoiding lockdowns while neighboring countries imposed restrictions, sparked controversy from the start. Even as mortality rates increased sharply in early 2020, Sweden kept shops, restaurants and most schools open. It banned public gatherings of more than 50 people and some restaurants were ordered to close temporarily, but most measures had little legal weight. While many people initially complied, they were less willing when the second wave hit in November, forcing tougher measures.

1. What arguments has this caused?

Lockdown skeptics saw the strategy as a way to avoid negative side effects of transmission control restrictions and as a model to contain the virus without violating personal freedom. Critics called it one deadly folly or outright disaster. Government supporters point to countries like the UK, Italy and Spain which, while locked, have a higher death rate than Sweden, while critics argue that the best comparison is with nearby countries such as Finland and Norway, which have similar population densities and coverage of the healthcare, but whose mortality and infection rates are well below those of Sweden.

2. Why did Sweden not close itself off?

Anders Tegnell, the state epidemiologist of Sweden and the main architect of the response, argued that all aspects of public health should be taken into account, including the adverse consequences of restricting people’s movements. Tegnell has said that Sweden has used proven methods of dealing with pandemics, while other countries “crazy ”when imposing lockdowns. Sweden instead relied primarily on people’s willingness to voluntarily adjust their lives to counter the transmission. There are also legal limits to the measures Sweden can take; while a temporary rule allowing the government to close stores is now in effect, Swedish law does not allow stay-at-home orders or curfews.

3. Was the goal to achieve immunity to the herd?

The Public Health Agency initially assumed that immunity in the population would eventually slow the transmission of viruses, although it denied the media reports that the goal was to achieve herd immunity by infecting segments of the population. Herd immunity, which blocks transmission, comes when enough people in a community have been immunized by infection or vaccination. Early calculations overestimate the number of unreported cases, leading experts to misjudge the population’s level of protection. Tegnell said in early May that at least 10% to 20% of people in Stockholm were infected, while three weeks later the agency found that no more than 7% of the capital’s population was infected. antibodies to the virus. When the second wave hit, Tegnell and his colleagues made it clear that Sweden couldn’t rely on the herd’s immunity to keep the virus from spreading.

4. Was this more about politics or science?

In Sweden, authorities such as the Public Health Agency have a great deal of autonomy and while the government has the final say, it relies heavily on their expertise. When the pandemic first hit Sweden in March, it was clear that the center-left government of Prime Minister Stefan Lofven would follow the approach outlined by the agency, and have continued to do so, even if the initiatives taken since November show some signs have shown. of a chasm. While Lofven has said publicly that he will continue to make decisions based on consultation with Tegnell and his agency, measures since November indicate a more active role for the government.

5. Has the strategy been abandoned?

Partly. From November 2020, Sweden began to introduce more significant restrictions, including a ban on the sale of alcohol after 8 p.m. in early 2021 and allowing schools to teach online from the seventh to ninth grades. Although the stores remained open, there were capacity limits. Most entertainment venues such as cinemas and theaters were forced to close due to an eight-person meeting meeting. The Public Health Agency has also modified its recommendations by asking people living with someone who is infected to quarantine and make mask recommendations, albeit only on public transport during rush hour. Yet there was no formal closure. Government response to Oxford Coronavirus Tracker, which gathers data on policies around the world related to virus control and shutdown, health systems measures, and economic support, showed that Sweden, which had the least stringent approach in Europe at the end of March to mid-April 2020, was in early 2021 had moved to the center of the pack.

Not exceptional

The Covid measures in Sweden are now just as strict as in most of Europe

Source: Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker

6. How bad is the death rate in Sweden?

At the end of January 2021, it had more than 11,500 people in Sweden died, or 113 per 100,000 residents. That was above the EU average, three times the death rate in Denmark and 10 times that of Norway. The most affected countries in Europe, including the UK, the Czech Republic and Italy, recorded more than 140 deaths per 100,000. The pandemic revealed flaws in Sweden’s institutions and healthcare system, similar to those elsewhere. Nursing homes were poorly prepared, the country had insufficient supplies of protective equipment, a lack of coordination halted efforts to ramp up testing, and intensive care capacity was less than half the European average. Sweden was also one of many countries that underestimated the rate at which the disease would spread and took action too late.

Deadly transmission

The death rate in Sweden is higher than the EU average, lower than in the US.

Source: Johns Hopkins University, Bloomberg

7. Has the strategy been successful?

Proponents claim that Sweden has shown that it is possible to control the virus without taking measures that restrict freedom and have an adverse effect on health. The World Health Organization does not endorse the Swedish strategy, but has emphasized the benefits of measures based on trust between authorities and the public. The recommendations made during the early stages of the pandemic had an impact on people’s behavior, with restaurant sales in Stockholm dropping between 75% and 80% at the end of March. After the December holidays, when many people stayed at home, there was a drop in infections, but authorities warned that Sweden could see a resurgence unless people follow social distance guidelines. There was also concern about it new variants of the virus, which led the country to restrict access from the UK, Denmark and Norway.

The Reference Shelf

- Bloomberg’s Lionel Laurent Opinion on how Sweden’s second wave struggled reality check.

- A Bloomberg Opinion column from Justin Fox on what it takes to get herd immunity.

- A Read quickly why the variants of the mutated coronavirus are so concerning.

- The regulations of the Public Health Agency of Sweden and guidelines to prevent transmission of Covid-19.

- A June 2020 Bloomberg article on Tegnell’s assessment of strategy.

- A October 2020 interview with Anders Tegnell about Sweden’s strategy.

- Correspondence in The Lancet by former state epidemiologist Johan Giesecke defending Sweden’s strategy. His assumption that between 20% and 25% of the Stockholm population was infected at the beginning of May was questioned by several critics.

- A report from the Swedish Royal Academy of Sciences, which contradicts the Public Health Agency’s view that there is no reliable evidence to support the use of face masks.

- A report on how the Swedish aged care system has dealt with the pandemic, prepared by a government appointed committee.