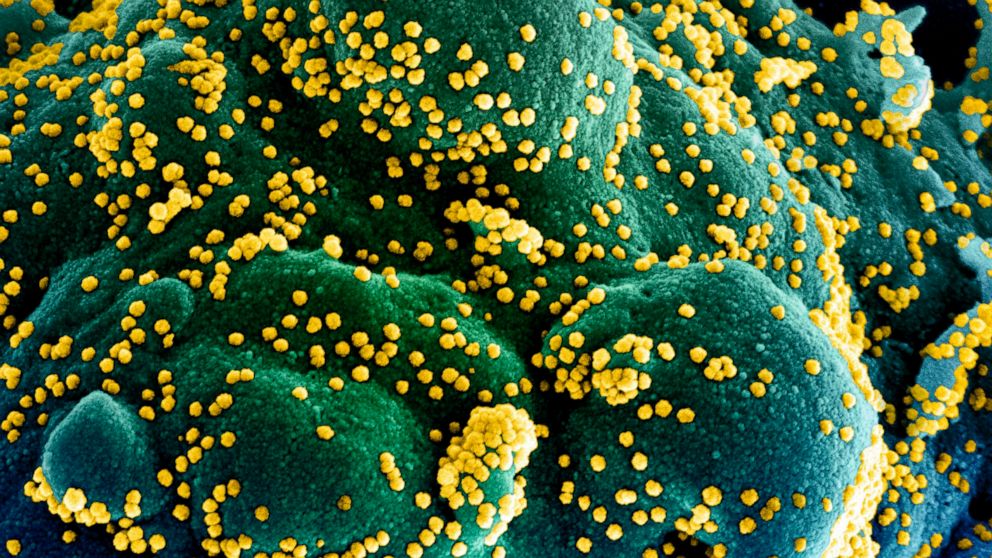

The monoclonal antibodies made in the lab could be a promising treatment for COVID.

As the push to get Americans vaccinated continues across the country, preliminary data has emerged that lab-made monoclonal antibodies may be a treatment for COVID-19.

Pharmaceutical company Regeneron said on Wednesday that its antibody cocktail appears to be holding up against the British and South African variants.

Researchers at Columbia University and scientists at Regeneron each independently confirmed the antibodies’ success in neutralizing both variants they tested it against.

The data is still preliminary and under peer review, but could indicate a useful tool if new mutations of the virus emerge.

Regeneron’s antibodies have not yet been tested against the Brazilian viral variant. However, Regeneron said it expects the cocktail to remain “as potent”.

Eli Lilly said on Tuesday that the combination of two antibodies was effective in COVID-19 patients at high risk of serious infection, reducing the risk of hospitalization and death by 70%, according to the results of a final phase of study.

That same day, Regeneron announced that its monoclonal cocktail had shown positive initial results with prophylactic use, preventing the virus in those who may have been exposed to the virus. Dr. George Yancopoulos, Regeneron’s Chief Scientific Officer, said he hopes the drug can “help break this chain” of active infection and transmission.

Eli Lilly also released data last week showing that the antibodies can help prevent disease and stop outbreaks among nursing homes.

Currently, Regeneron’s cocktail of casirivimab and imdevimab, and Eli Lilly’s single bamlanivimab have received an emergency permit from the Food and Drug Administration. They are intended for use in the early stages of infection for non-hospitalized patients 65 years of age and older and for those at high risk of serious illness to keep them out of the hospital. The cocktails must be administered within days of diagnosis and are only intended for people with moderate to severe symptoms.

The government has spent millions of dollars to make doses available to anyone who qualifies for them.

Such therapies can be an important tool for mitigating severe cases, while also relieving some of the pressure on pressurized health care systems.

The news from Eli Lilly may point to an important milestone: Combined antibodies bamlanivimab and etesevimab, working together, could prove effective against a “wider range” of COVID-19 variants, company representatives said. This could be an essential tool as mutant strains continue to emerge.

With the new data in hand, Eli Lilly said it plans to initiate global submissions for its combination therapy and to apply for an emergency permit for the use of the single antibody bamlamnivimad as a “passive vaccine” treatment after exposure in nursing homes. .

The use of “passive vaccines” of monoclonal agents could provide emergency protection, acting immediately against the virus, until enough of the population receives the vaccine needed to achieve herd immunity.

The FDA has yet to review last week’s developments from both Eli Lilly and Regeneron to determine whether the companies can market these drugs for these new purposes and in these new forms.

The limited authorization under which Eli Lilly and Regeneron are currently operating has been rolled out in infusion centers across the country, with the Department of Health and Human Services developing an interactive, national mapping tool to help pinpoint where monoclonal antibody therapy has recently been received and available for use.

Yet despite their availability and encouraging safety and efficacy profiles, US acceptance of the therapies has been slow and “disappointing” – by the end of 2020, only 20-25% of the supply had been used.

In addition to a lack of public awareness, a cumbersome infusion process and staff hampered higher use of the therapies: health care systems “crash,” said Dr. Janet Woodcock, chief of therapeutics for Operation Warp Speed, mid-January. . Meanwhile, medical personnel are needed to assist with the administration of IVs, even if ICUs badly need them too.

Sony Salzman and Eric M. Strauss of ABC News contributed to this report.