Space exploration has achieved several notable firsts in 2020 despite the COVID-19 pandemic, including commercial manned space flights and the return of samples from an asteroid to Earth.

The coming year promises to be just as interesting. Here are some of the missions to keep an eye out for.

Artemis 1

Artemis 1 is the first flight of the NASA-led international Artemis program that will return astronauts to the moon by 2024. This will consist of an unmanned Orion spacecraft that will be sent around the moon on a three-week flight. IT will reach a maximum distance from Earth of 450,000 km – the furthest in space that any spacecraft capable of transporting humans will ever have flown.

Artemis 1 will be launched into orbit on the first Nasa Space Launch System, which will be the most powerful rocket in operation. From orbit, the Orion will be propelled on a different path to the Moon by the rocket’s intermediate cryogenic propulsion phase. The Orion capsule will then travel to the Moon under the power provided by a service module provided by the European Space Agency (Esa).

The mission gives engineers back on Earth the opportunity to evaluate how the spacecraft is performing in deep space and serves as a prelude to later manned lunar missions. The launch of Artemis 1 is currently scheduled for the end of 2021.

Mars missions

In February, Mars will receive a fleet of terrestrial robot guests from different countries. The United Arab Emirates’ Al Amal (Hope) spacecraft is the Arab world’s first interplanetary mission. It is scheduled to arrive in orbit on February 9, where it will spend two years tracking the weather on Mars and its disappearing atmosphere.

Within weeks of Al Amal, the China National Space Administration’s Tianwen-1, consisting of an orbiter and a surface rover, arrives. The spacecraft will orbit Mars for several months before deploying the rover to the surface. If successful, China will become the third country to land anything on Mars. The mission has several objectives, including mapping the mineral composition of the surface and looking for deposits under surface water.

Nasa’s Perseverance rover will land in Jezero Crater on Feb. 18, looking for signs of ancient life that may have been preserved in the clay deposits there. Critically, it will also store a cache of Mars surface samples on board as the first part of a highly ambitious international program to return samples from Mars to Earth.

Chandrayane-3

In March 2021, the Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) is planning its third moon mission, Chandrayaan-3. Chandrayaan-1 was launched in 2008 and was one of the first major missions in the Indian space program. Consisting of an orbiter and a surface penetrator probe, the mission was one of the first to confirm evidence of lunar water.

Unfortunately, contact with the satellite was lost less than a year later. Unfortunately, there was a similar accident with its successor, Chandrayaan-2, which consisted of an orbiter, a lander (Vikram) and a lunar rover (Pragyan).

Raymond Cassel / Shuttestock

Chandrayaan-3 was announced a few months later. It will only consist of a lander and a rover, since the orbiter from the previous mission is still functioning and providing data.

If all goes well, the Chandrayaan-3 rover will land in the Aitken Basin at the moon’s south pole. It is of particular interest because it is thought to be home to numerous deposits of underground water ice – an essential component for any future sustainable habitation of the moon.

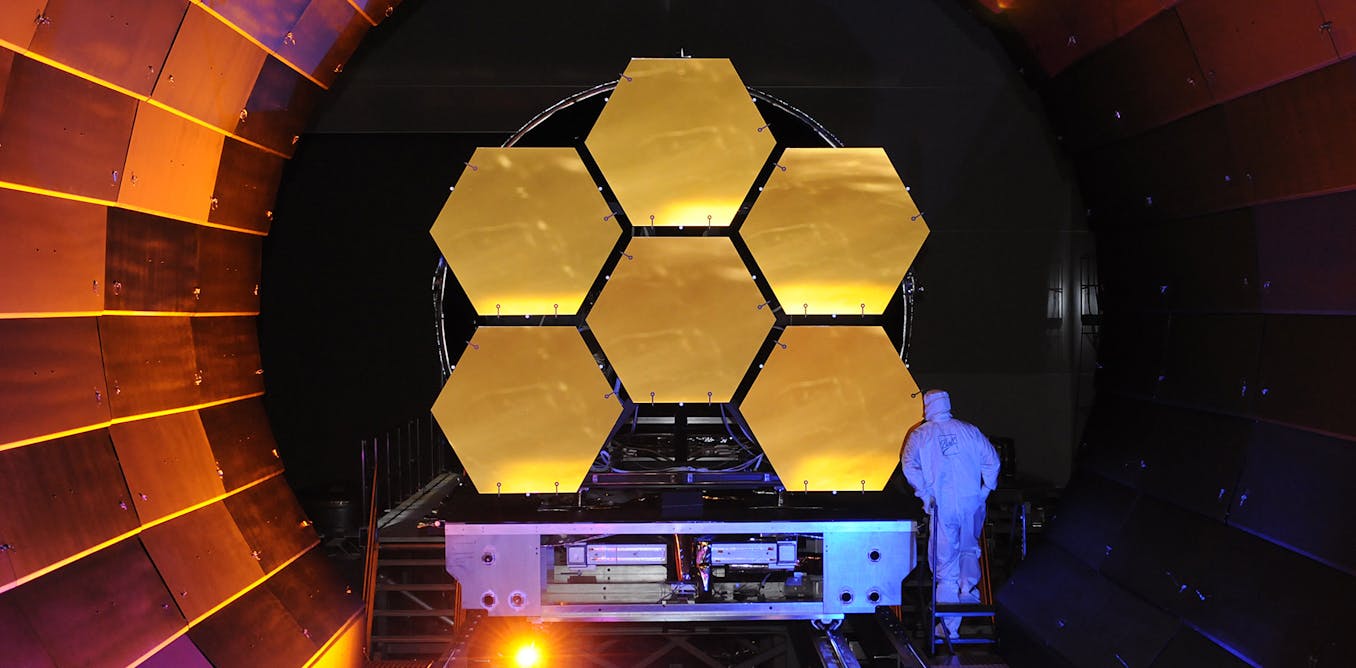

James Webb space telescope

The James Webb Space Telescope is the successor to the Hubble Space Telescope, but has had a rocky path to be launched. Originally slated for launch in 2007, the Webb telescope is nearly 14 years late and has cost about US $ 10 billion (£ 7.4 billion) after apparent underestimations and overshootings comparable to Hubble’s.

While Hubble has provided some amazing images of the universe in the visible and ultraviolet regions of light, Webb plans to focus observations in the infrared wavelength band. This is because when observing very distant objects, gas clouds are likely to get in the way.

Esa / Hubble & Nasa, J. Lee and the PHANGS-HST team;CC BY-SA

These gas clouds block very small wavelengths of light such as X-rays and ultraviolet light, while longer wavelengths such as infrared, microwave and radio can penetrate more easily. So by observing in these longer wavelengths, we should see more of the universe.

Webb also has a much larger mirror with a diameter of 6.5 meters compared to Hubble’s mirror with a diameter of 2.4 meters – essential for improving image resolution and seeing finer details.

Webb’s primary mission is to look at light from galaxies at the edge of the universe, which can tell us about how the first stars, galaxies and planetary systems came to be. This may also contain some information about the origin of life, as Webb plans to map the atmospheres of exoplanets in detail, looking for the building blocks of life. Do they exist on other planets, and if so, how did they get there?

We will also likely be treated to some stunning images similar to Hubble’s. Webb is currently scheduled to launch on October 31 with an Ariane 5 rocket.