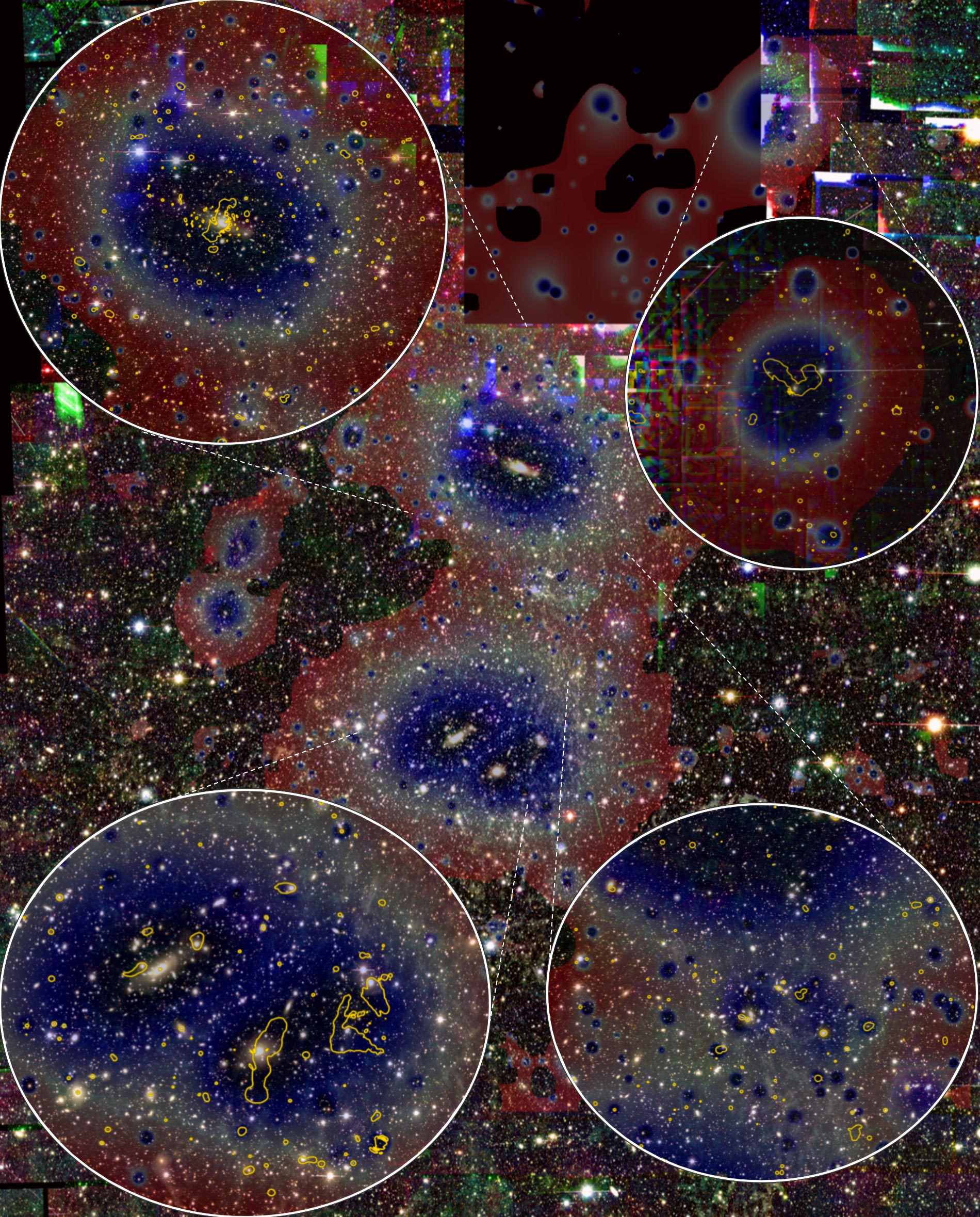

Optical image of the Abell 3391/95 system made with the DECam camera. Superimposed on each other are the eROSITA image (darker = higher gas density) and radio contours (yellow) of the ASKAP telescope. Credit: Reiprich et al., Astronomy & Astrophysics

More than half of the matter in our universe has been hidden from us so far. Astrophysicists, however, suspected where it might be: in so-called filaments, inscrutably large thread-like structures of hot gas that surround and connect galaxies and galaxy clusters. A team led by the University of Bonn has now observed a gas filament with a length of 50 million light years for the first time. The structure is strikingly similar to the predictions of computer simulations. Perception thus also confirms our ideas about the origin and evolution of our universe. The results are published in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics.

We owe our existence to a minor deviation. Almost exactly 13.8 billion years ago, the Big Bang occurred. It is the beginning of space and time, but also of all the matter that makes up our universe today. Although initially concentrated at one point, it expanded at lightning speed – a gigantic cloud of gas in which matter was distributed almost evenly.

Almost, but not quite: in some parts the cloud was a bit denser than in others. And for this reason alone there are planets, stars, and galaxies today. This is because the denser regions exerted slightly higher gravitational forces, pulling the gas from their surroundings towards them. More and more matter was therefore concentrated in these regions over time. However, the space in between became emptier and emptier. Over the course of more than 13 billion years, a kind of sponge structure developed: large “holes” without any matter, with in between areas where thousands of galaxies gather in a small space, so-called clusters of galaxies.

Still image of a simulation showing the distribution of hot gas (left), compared to the eROSITA X-ray image of the Abell 3391/95 system (right). Credit: Reiprich et al., Astronomy & Astrophysics

Fine web of gas wires

If it really happened that way, the galaxies and clusters would still have to be connected by remnants of this gas, like the gossamer threads of a spider web. “According to calculations, more than half of all baryonic matter in our universe resides in these filaments – this is the form of matter that makes up stars and planets, just like ourselves,” explains Prof. Dr. Thomas Reiprich from the Argelander Institute of Astronomy at the University of Bonn. Yet so far it has escaped our sight: due to the enormous expansion of the filaments, the matter in it is extremely diluted: it contains only ten particles per cubic meter, which is far less than the best vacuum we can create on Earth.

With a new measuring instrument, the eROSITA space telescope, Reiprich and his colleagues were now able to make the gas fully visible for the first time. “EROSITA has very sensitive detectors for the type of X-rays emitted from the gas in filaments,” explains Reiprich. “It also has a large field of view – like a wide-angle lens, it captures a relatively large portion of the sky in a single measurement, and at very high resolution.” This allows detailed images to be made of such enormous objects such as filaments in a relatively short time.

In this representation of the eROSITA image (right; left another simulation for comparison), very faint areas of thin gas are also visible. Credit: Left: Reiprich et al., Space Science Reviews, 177, 195; right: Reiprich et al., Astronomy & Astrophysics

Confirmation of the standard model

In their study, the researchers examined a celestial body called Abell 3391/95. This is a system of three galaxy clusters about 700 million light-years away. The eROSITA images show not only the clusters and numerous individual galaxies, but also the gas filaments that connect these structures. The entire filament is 50 million light years long. But it could be even more massive: the scientists assume that the images only show part.

“We compared our observations with the results of a simulation that reconstructs the evolution of the Universe,” explains Reiprich. “The eROSITA images look remarkably like computer generated images. This suggests that the generally accepted standard model for the evolution of the universe is correct. Most importantly, the data shows that the missing matter is probably actually hidden in the filaments.

Reiprich is also a member of the Transdisciplinary Research Area (TRA) “Building blocks of matter and fundamental interactions” at the University of Bonn. Scientists from the most diverse faculties and disciplines come together in six different TRAs to collaborate on future-relevant research themes of the University of Excellence.

Reference: “The Abell 3391/95 cluster system of galaxies. A 15 Mpc intergalactic medium emission filament, a warm gas bridge, clumping matter and (re) accelerated plasma discovered by combining SRG / eROSITA data with ASKAP / EMU and DECam data ”by TH Reiprich, A. Veronica, F. Pacaud, ME Ramos-Ceja, N. Ota, J. Sanders, M. Kara, T. Erben, et al., Accepted, Astronomy and Astrophysics.

DOI: 10.1051 / 0004-6361 / 202039590

Participating institutions and funding:

Nearly 50 scientists from institutions in Germany, the US, Switzerland, Chile, Australia, Spain, South Africa and Japan took part in the study.

eROSITA was developed with funding from the Max Planck Society and the German Aerospace Center (DLR). The telescope was launched into space last year aboard a Russian-German satellite whose construction was supported by the Russian space agency Roskosmos. This work also used the Dark Energy Camera (DECam) on the Víctor M. Blanco 4-meter telescope from Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory, a program from NSF’s NOIRLab, and the Australian Square Kilometer Array Pathfinder (ASKAP) telescope, built and operated by CSIRO (Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization). The current study was funded by various research funding organizations in the participating countries.