In the southern United States, deadly ‘brain-eating amoeba’ infections have occurred in the past. But cases have appeared further north in recent years, likely due to climate change, a new study finds.

The study’s researchers, from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), examined cases of this brain-eating amoeba, known as Naegleria fowleri, over a period of four decades in the US.

They found that while the number of cases that occur each year has remained roughly the same, the geographic range of these cases has shifted north, with more cases emerging in the Midwestern states than before.

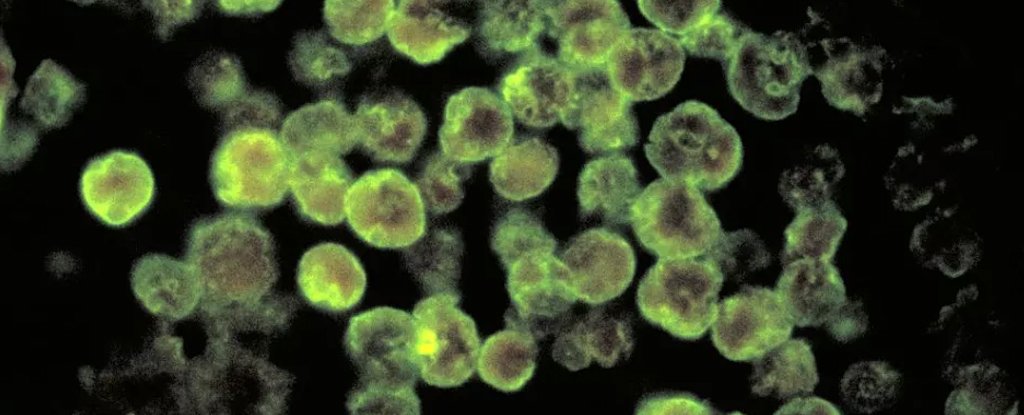

N. fowleri is a single-celled organism found naturally in warm fresh water, such as lakes and rivers, according to the CDC. It causes a devastating brain infection known as primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM), which is almost universally deadly.

Infections occur when contaminated water passes through a person’s nose, allowing the organism to enter the brain through the olfactory nerves (responsible for your sense of smell) and destroy brain tissue. Swallowing contaminated water will not cause infection, the CDC says.

Because N. fowleri Thriving in warm waters, down to 113 degrees Fahrenheit (45 degrees Celsius), it’s possible that global warming could affect the geographic range of the organisms, the authors said.

In the new study, published Wednesday (Dec. 16) in the journal Emerging infectious diseases, the researchers analyzed American cases of N. fowleri linked to recreational water exposure – such as swimming in lakes, ponds, rivers, or reservoirs – from 1978 to 2018.

They identified a total of 85 cases of it N. fowleri that met their criteria for the study (ie, cases related to recreational water exposure and including location data).

During this time, the number of cases reported annually was fairly constant, ranging from zero to six per year.

The vast majority of cases, 74, occurred in Southern states; but six were reported in the Midwest, including Minnesota, Kansas, and Indiana. Of these six cases, five occurred after 2010, the report said.

(CDC, Emerging Infectious Diseases, 2021)

(CDC, Emerging Infectious Diseases, 2021)

Above: Cases of N. fowleri infections associated with recreational water, 1978 to 2018.

What’s more, when the team used a model to examine trends in the maximum latitude of cases per year, they found that the maximum latitude had shifted about 8.3 miles north per year during the study period.

Finally, the researchers analyzed weather data from around the date each case occurred and found that the mean daily temperatures in the two weeks prior to each case were higher than the historical mean for each location.

“It is possible that rising temperatures and the resulting increases in recreational water use, such as swimming and water sports, may contribute to the evolving epidemiology of PAM,” the authors wrote.

Attempts to characterize PAM cases, such as knowing when and where these cases occur, and being aware of changes in their geographic range, can help predict when it is most risky to visit natural swimming holes, the authors said.

There is no quick test for that N. fowleri In water, the only sure way to prevent these infections is to avoid swimming in warm fresh water, the CDC says.

If you choose to swim in warm fresh water, you can try to prevent water from flowing through your nose by keeping your nose closed, using nose clips, or keeping your head above water.

This article was originally published by Live Science. Read the original article here.